Light house

Posted on Nov 29, 2019 by Alex Fice

IBC was a hotbed of new lighting technology, some on booths and some hiding behind the scenes. Here are a few of the highlights.

Words Phil Rhodes

The biggest single-source LED movie light currently made is rated at around 3KW. The biggest HMIs are 24KW. That means that LED has some way to go before it can completely replace the gear that’s been in use for decades.

575W HMIs are the smallest common type and perhaps something of a watershed: once LED has started to compete at that level, the technology will really be coming of age. Matching 575W HMI, however,

would require something not much less than a 575W LED, and a 575W single-emitter LED hard light has long been a tough thing to make. Even so, looking at some representative specimens from IBC2019, it’s clear that the race to do that is well underway.

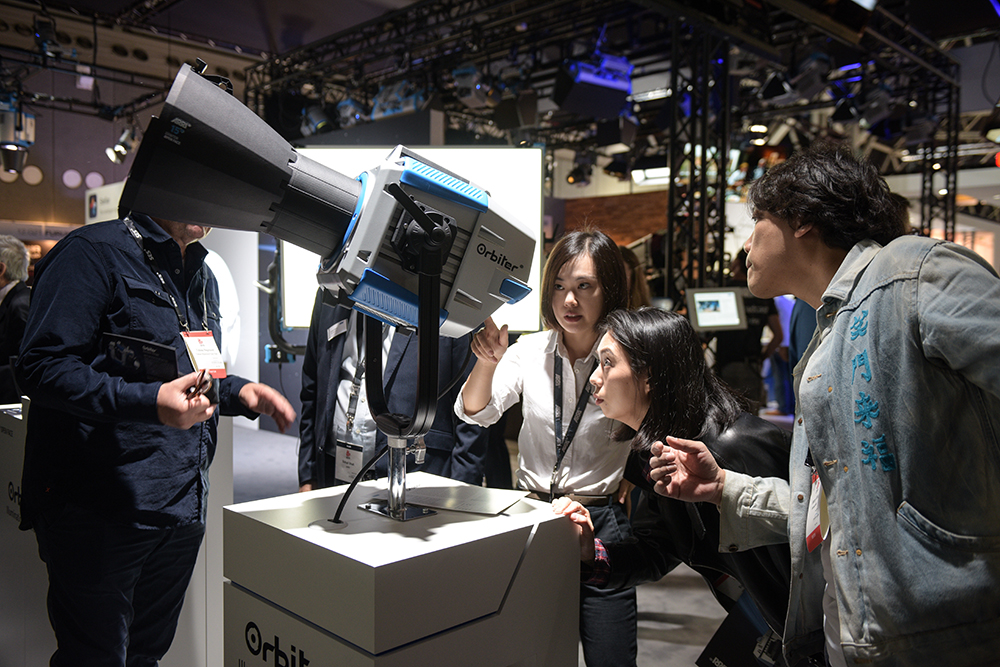

Arri Orbiter

The entrance to IBC’s Hall 12 this year was guarded by Arri’s Orbiter. The company has a lot of experience in LED hard light, having been early to offer a range of Fresnels, though the Orbiter is more complex – perhaps an attempt to create a light that’s all things to all people. The promotional material mentions “sheer output” as a feature, and while the power level is more or less similar to an L10 Fresnel at around 500W, with the efficient, open-faced reflectors, the Orbiter should liberate more photons overall. Like anything at this power level, the Orbiter is just about usable away from a mains socket, requiring 48V input from a big floor-standing block battery.

With a more cynical eye, it’s also a light with the sort of interchangeable optical components – reflectors, diffusers and so on – that have been available from other manufacturers for a while, though not with full colour mixing and not at this power level (though see the upcoming Hive Super Hornet). Speaking of colour, among the controls is an option to select by CIE xy coordinate, a welcome option found mainly at the high end, which should make it easier to colour match different lights.

It’s hard to tell whether LED will eventually scale up big enough to replace absolutely every other competing technology

The reflectors closely approximate a PAR and, like any PAR, the beam is not as clean as that from a Fresnel. It does seem a little cleaner than an HMI-based PAR, possibly because the hexagonal LED array is a more consistently illuminated source. There are also projection (profile or ellipsoidal) adapters, dome and panel diffusers. It will do more or less anything, though we don’t yet know what it’ll cost.

Aputure LS 600D

Someone with simpler desires might be tempted by Aputure’s announcement of a 600W light, the 600D. Again, there’s no price, and best guesses put release any time before NAB next year.

The key feature is that all of those 600 watts are dedicated to making daylight, and the output is prodigious. In fact, some of Aputure’s existing Bowens S-type accessories aren’t qualified for use on the 600D, on the basis that the blast of light is so ferocious, it might melt plastic parts. The world isn’t used to LEDs that can so easily set fire to the curtains.

One accessory that is compatible, being made entirely from metal and glass, is Aputure’s existing spotlight mount. In combination with the 600D, it should create a really attractive alternative to the widely admired Jo-Leko combination of a K5600 Joker-Bug HMI with an ETC Source Four lens tube. The difference is that even the less-capable 400W Jo-Leko kit costs US$3490, and we can reasonably hope that the 600D will be less than that.

LED, fluorescent and HMI all need power conditioned in various ways, and the power conditioner is not a loss-free device

The power controller shown at IBC is temporary and should, the company thinks, get smaller. Four 14.4V V-Mount batteries are required to power the 600D at full blast, and even then, they’ll naturally be asked to sustain a 150W load – more, actually, since the company accepts the power controller is not 100% efficient. That’s a stern test for many camera batteries. In the end, though, this light is a clear and direct response to the need for a cheaper 575W HMI, and that’s a good thing.

Ways of efficiency

Comparing LED efficiency to technologies such as HMI and fluorescent is difficult, because the effectiveness with which the emitter converts electrons to photons is only part of the equation. LED, fluorescent and HMI all need power conditioned in various ways, and the power conditioner is not a loss-free device. Then there’s the lamp house: the traditional Fresnel, for instance, offers a lot of flexibility, but it’s obvious to anyone who’s ever looked inside that lots of the bulb’s energy simply collides with the case. LEDs don’t emit light in the same way bulbs do, which is why a lot of LED lights are open-faced at least by default – and it’s no secret that more photons come out of a PAR than a Fresnel of the same power.

Nanlite Forza 500

Perhaps not coincidentally, the Nanlite Forza 500 is also a clear response to the need for a cheaper 575. Parent company Nanguang has been manufacturing lighting for some time, and while much of it has been aimed at the most price-conscious part of the market, the Nanlite brand is clearly more ambitious. The Forza 500 monolight is available right now for a shade less than $2000.

It’s 17% less powerful than the Aputure, but otherwise pretty comparable: both are reasonably small-source LED lamp heads, taking Bowens S-type accessories with separate power controllers. The Forza 500 is perhaps a little shorter, the lamp head itself is a featherweight at 2.5kg, and the power controller wants a pair of (rather expensive) 26V V-Mount batteries as opposed to the four 14.4V camera batteries preferred by Aputure. What’s most interesting about this, though, is that the existence of two such similar products highlights how big a market everyone seems to be expecting.

Hive Super Hornet 575-C

To find something that’ll compete directly with Arri, we have to look at Hive. The company showed a very early prototype of its 500W full colour mixing LED at NAB, though we had to wait until September to see a more final version. Hive began making lights using microwave plasma technology, but has since specialised in colour mixing LED hard light, a niche that’s tricky to carve out, because all of the heat is generated in one small spot.

The Super Hornet 575 is apparently as powerful as a 575W HMI, despite consuming less power – something that’s sometimes justified by the idea that losses from the electronics of an LED driver are often less than in an HMI ballast. Either way, the Super Hornet retains Hive’s long-established four-inch diameter body and is about a foot long to make room for the necessary heat sinks. It’s therefore significantly smaller and lighter than an Orbiter, but does some very similar things, with a very similar accessory selection.

Hive lists a price of $5,262.11 on its website. How that compares to an Orbiter remains to be seen, and the two differ in many ways: the Orbiter is a unified device incorporating a large LCD display and controller, while the Super Hornet is a clean cylindrical design with separate power controller and head. The Super Hornet has no weather resistance, though, perhaps as a consequence, it is a lot smaller and lighter.

Medium-sized LED hard lights, then, are just starting to nibble at the toes of HMI, while simultaneously pushing out of the area where they can realistically be battery powered. Meanwhile, something much bigger is happening in the higher-power world of big studio lighting.

Ways of colour

It’s no big secret that putting a red, green and blue LED together doesn’t actually create white light. It may create something that looks a bit like white light, but viewed on a colour meter, it’s still clearly three spikes on a spectrum. Point that light at something that reflects only – say – bright yellow light, and things won’t look right. LED lights can be phosphor converted, where a blue LED causes a red or green phosphor to glow, which creates a broader, less spiky spectrum, but any reasonable full colour-mixing LED light will still need to use four, five, six or even more channels, including one or two whites, for good performance. With every manufacturer using a different approach, it’s often possible to make two lights look and work the same – but measure the actual output spectrum, and things can be quite different.

Creamsource SpaceX

At IBC2019, Creamsource showed its SpaceX light, which is designed either to drive a conventional spacelight skirt or, with additional optics, to act as a ‘punch light’, perhaps to drive diffusion or provide a backlight. The SpaceX is perhaps a replacement for the existing Creamsource Sky, which accepted a degree of bulk and 23kg weight in return for fanless operation. The SpaceX is smaller and lighter at 18kg thanks to active cooling.

At 1200W, SpaceX is an absolute beast and, as with most high-power LED applications, it uses a cluster of six emitter modules. There’s full colour mixing, support for unique accessories such as the Flashbandit synchronisation device, and Creamsource’s traditionally sturdy and attractive approach to the mechanical engineering. The control system offers CIE xy colour selection. And, importantly, it’s not a fortune: at $6500, the price per watt is hugely competitive.

LED spacelights are efficient, sure, and that’s especially relevant where expensive studio power is concerned. Unlike the little half-kilowatt hard lights, though, they’re also lightweight, and the reduced power consumption makes cabling and rigging vastly easier. That, in turn, makes power distribution smaller, lighter and cheaper, and requires fewer people over less time to set up. The driving force behind a lot of this is not just more efficient light.

In the end, products just such as SpaceX, and related products from Sumolight and Lightstar, represent one part of the market; the smaller hardlights represent another. Both, though, are striving for power. It’s hard to tell whether LED will eventually scale up big enough to replace absolutely every other competing technology, but that certainty seems to be the trajectory we’re on in late 2019.