Production: Avatar: Fire and Ash

Posted on Feb 20, 2026 by Admin

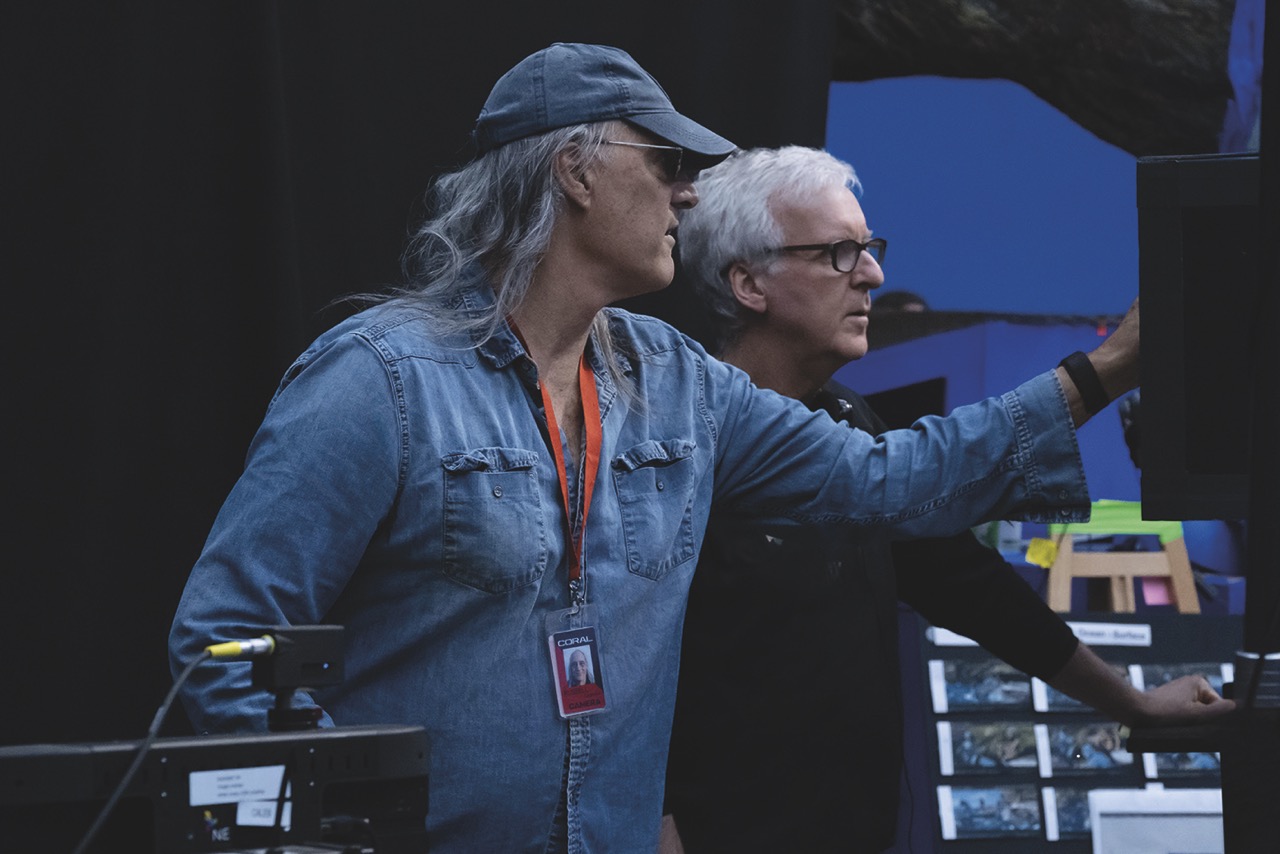

DOP Russell Carpenter, ASC talks virtual scouting, performance capture and lighting Pandora in the latest Avatar instalment

Words Oliver Webb | Images Disney

Top image 20th century studios

Fire and Ash (2025) is the third instalment in James Cameron’s Avatar franchise. Following the events of The Way of Water (2022), the conflict on Pandora escalates as Jake and Neytiri’s family encounter a new, aggressive Na’vi tribe (the Mangkwan clan) led by Varang.

Russell Carpenter, ASC first worked with Cameron on the 1994 film True Lies. “After that, I shot the test for Titanic,” he begins. “Someone else was going to do it, then it turned around and landed in my lap again which was very fortunate.” It wasn’t until The Way of Water that the two would collaborate again. They shot it and Fire and Ash simultaneously.

Filming for both began as early as 2017 and wrapped in 2020, with extra pick-up dates required for Fire and Ash. “It is such an outlier to almost everything else done recently,” Carpenter says. “It is its own ecosystem doing these films.”

Carpenter describes how the initial steps of the Avatar films centre around the script. Production designers then start workshopping ideas, which they present to the director. “Jim [Cameron] then does virtual location scouting with his virtual camera,” adds Carpenter. “The whole planet of Pandora is built in computers. When Jim walks out on the stage it is obviously quite a bland and empty space, but he will start pointing the virtual camera in different directions and suddenly you will see these big monitors all over the place and there will be all of these amazing waterfalls and so on.”

After the layout is where Cameron wants it to be, people are brought in to block out the scenes before the actors come onboard and the performances begin to take shape. “The actors wear performance capture suits, and it is very important to make sure that there are no distractions so Jim can really hone in on their performance. I finally come onto the project at this point, like the alien from the world of living creatures, rather than CGI creatures.”

Carpenter compares this process to a layer cake. “On other films you are going from A to B to C and your destination basically,” he says. “Here, you have got a cosmos where all of this information is flowing around all the time, constantly being updated. It is a hive of different minds and departments. As a DOP, I am not getting all the information I need in one coherent package because it is still being worked on as we go. People had been working on this film for six years before I even came onboard. It’s how these films are made.”

Carpenter spent a year lighting CGI scenes before he could see it all embedded together. “It’s my one job to seamlessly fuse the human characters, especially Spider, into a world that is completely CGI,” he says. “You want to take the viewer on an immersive journey and not do anything with the technology that bumps the viewer out of that.”

Cameron creates virtual shots that are displayed on the on-stage monitors. It is then down to Carpenter and his crew to convert the footage. “We can see exactly where his camera went, how high it was, how fast it was moving etc and be able to replicate that with our live action camera,” he explains. “We must also make sure we have enough room on the stage to do what Jim just did. While he’s in his virtual world, we need to make sure we don’t go off the stage.”

Shooting the two instalments at the same time proved to be a vital decision due to actors aging out of their roles. “When I first met Jack Champion (Spider), he was a little kid,” says Carpenter. “I called him tadpole. By the time we shot the film the pressure was on because he’s getting older and you can see his facial structures subtly changing. There was a ticking clock on how long he would still look like the age he was supposed to be.”

In the middle of production, the crew returned to the water stages in Manhattan Beach to shoot additional scenes before Covid-19 derailed further plans. “Many months were lost. Filming was unable to resume in Wellington. It took a lot of doing to be the first film that would re-enter New Zealand to shoot,” acknowledges Carpenter. “It changed the pace of how we shot and was essential to some of the challenges

we faced making these films happen.”

Carpenter observes how the aesthetic of The Way of Water and Fire and Ash are very similar, as they were initially meant to be just one film. He points to the setting of Bridgehead City as one of the key distinctions between them. A colossal base established by the Resources Development Administration near the Pandoran oceans, Bridgehead was introduced in The Way of Water but featured heavily in Fire and Ash.

For the Bridgehead sequences, Carpenter opted for unpleasant, more caustic light that was influenced by Kmart parking lots in the seventies and eighties. “We wanted something really aesthetically different to the Na’vi’s environments, who live in this sort of groovy hippie world. Bridgehead consists of harsh lighting, very straight lines and nothing sinuous and alive as in the world of Pandora.”

In terms of his lighting approach for the Pandora forest sequences, Carpenter explains that they could be very fluid in what they were doing. “We wanted to keep the lighting high up off the ground and out of the way,” he says. “Jim said he wanted the forest exteriors to have three distinct colours – warm sunlight, cool tones and light bouncing up from the plants. This always-shifting light then helped shape the Na’vi in an interesting and dynamic way.”

Carpenter compares the nature in the film to the Hudson River School, as well as the works of J M W Turner. “It’s this idea that man has a place in nature,” he tells us. “You would often see these amazing landscapes and the way that the sunlight was hitting them – or how the colours were pulled apart. There may be a human being somewhere in the corner to give everything the immensity of scale. This idea played out in the visual design of Avatar. We tried to place the Na’vi in a natural surrounding and feel that light.”

Carpenter relied on the Sony CineAlta VENICE Rialto 3D paired with FUJINON MK and Cabrio lenses to capture the film. “Jim’s dictum was that he wanted the camera system to weigh less than the one used for the first instalment,” concludes Carpenter. “He was working with Sony for years to come up with a camera that fit the bill technically but also could be taken apart, so you could have the lenses and the sensor inside your 3D rig. A month or so before we were set to film, Sony came up with the actual technology. Jim’s theory was that we don’t have the technology now, but we’re going to have it by the time we shoot. That’s a daring game to play, but it worked out.”

This story appears in the February/March 2026 issue of Definition