Real and Unreal

Posted on Mar 25, 2022 by Alex Fice

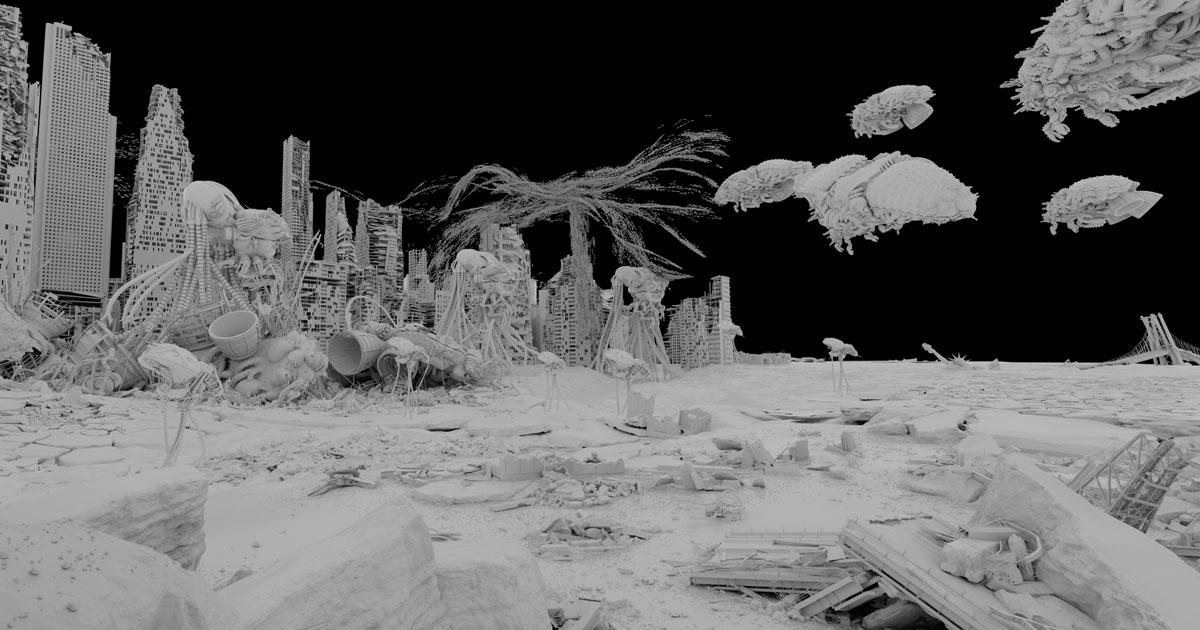

In this VFX special, DNEG’s Huw Evans breaks down the groundbreaking and meta visual effects used to create the dojo, Exo-Morpheus, the Mega City and the legendary foetus fields

Words Chelsea Fearnley / Images DNEG © 2021 Warner Bros

In 1999, John Gaeta’s VFX team at Manex managed to pull off the impossible, with the Oscar-winning bullet time effect. Using multiple cameras to create the illusion of time slowing down or standing still, it is a visual impression that has since been referenced and used in feature films and video games – changing VFX forever. It’s unsurprising, then, that when Lana Wachowski decided to return to the world of The Matrix two decades later for The Matrix Resurrections, there was apprehension amongst the VFX department about how to up the ante. It’s now much easier to create photorealism, thanks to advances in capture technology. However, the director didn’t want the visual effects to overpower the beautiful love story between Neo and Trinity.

“It’s an upgrade, but where the visuals from previous films were concerned with blurring the lines between reality and unreality, Resurrections feels more relatable. It’s a metaverse that’s equal parts sequel, remake and homage,” explains DNEG VFX supervisor Huw Evans. “It’s a love story.”

The Matrix Resurrections opens with a familiar retread of the first movie’s opening scene, but doesn’t include the bullet time shot. The effect was a point of careful consideration, with Wachowski cognisant about trying to imitate themselves too directly and risk losing the edge of being self-aware. In fact, there is no real bullet time like in the first film. Instead, the characters can move at different speeds – faster than a bullet. This was achieved through use of stereo rigs capturing two frame rates (24fps and 120fps) simultaneously. Therefore, enabling the team to shoot the same scene at two different speeds for compositing in the edit.

The dojo

DNEG, split between its London and Vancouver offices, created 723 shots for the film. It was responsible for moments in the ‘real world’, including the training dojo in which an epic fight between Neo and Morpheus occurs. The scene was created entirely in Unreal Engine and is based around Germany’s Rakotzbrücke, an arched bridge that creates a perfect circle when reflected in the glass-still waters below.

“We received the scene from Epic and readjusted as we progressed it, adding details such as rippling waters, swaying trees and falling leaves,” explains Evans. “Our plan was to push real-time rendering in Unreal to get final quality renders that would hold up at 4K. But building the Unreal pipeline was a challenge.”

The team started with version 4.25 of Unreal. However, it didn’t have the tools needed to use images in their pipeline, such as OCIO colour support and rendering passes separately. These features are now available, but are a result of close dialogue between the Epic Games team and DNEG.

“It was super exciting to be at the forefront of driving forward how Unreal Engine can be used,” explains Evans. “If we were to do it again, having set-up for the painful technical issues, it would be a lot smoother. Nonetheless, the ability to quickly block out the cut, and figure out lighting direction and how it was going to look through the camera, was an incredibly big thing for us – as was being able to view it at a decently rendered quality.”

Exo-morpheus

Another challenge for DNEG, both technically and artistically, was creating the physical manifestation of Morpheus’ digital self. In The Matrix world he’s human, but in the real world he’s an exomorphic particle codex, characterised by animated ball bearings.

“In the conception stage, Lana gravitated towards creating Exo-Morpheus (as he’s referred to by cast and crew) as an elegant, abstract and fluid character. We did some proof of concepts – effects tests on how he would move. We realised that for him to be a main character captured up-close, delivering convincing dialogue, he would need to settle into a more humanoid form and be less ethereal. Then the audience could relate to him and understand him visually,” reveals Evans. “We decided his ball bearings should solidify into a more solid surface, depending on where his focus is. So, if he was having a conversation with somebody, the back of his head would be animated, and his face would be solid. Similarly, if he was to extend his arm and shake someone’s hand, his arm would solidify and come together for a nice, solid handshake, then become fluid

again once it relaxes.”

Multiple witness cameras were used to capture the performance. Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, who plays Morpheus, wore full head-to-toe body tracking, so that the team could get a reference for contrast and shapes in greater detail. DNEG then treated him as they would a normal CG character, doing muscle and skin simulations to provide an underlying layer of reality and physicality – even though none of this would be apparent to viewers. Evans explains, “When we did our simulation of the ball bearings, they were reacting to his muscles and skin, particularly around his face. To capture all of those subtle movements, it was important that we went through all of the character build steps before we got to the effects-driven stuff.”

Read the full article here.