Rise of the Robots

Posted on Jul 19, 2022 by Samara Husbands

From Terminator’s T-1000 to the sentinels of The Matrix, machines often play arch-enemy in front of the camera. But behind it, they’re more helpful than Optimus Prime

Words. Phil Rhodes | Images. Various

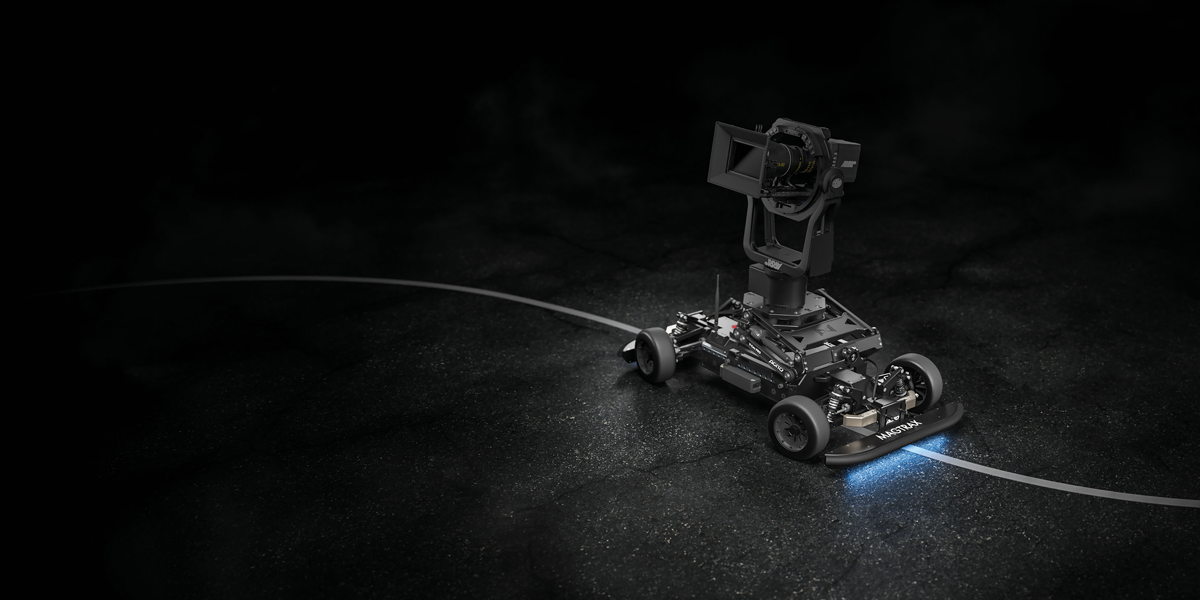

As electronics have exploded in potential, camera support gear that might once have been simply mechanical has moved into the realm of active robotics. Putting a camera in the right place is increasingly a collaboration between smart grips and smart machines.

Perhaps the best example is Steadicam, which began life as a purely mechanical device and largely remained so, other than occasionally having gyroscopes strapped on (they’re not, contrary to popular misconception, part of the basic concept). Ever since microscopic gyros became possible, though, Steadicam-style designs have enjoyed everything from auto horizon levelling to the Arri Trinity model, combining gimbal and Steadicam stabilisation for a go-anywhere solution.

The latest innovation from the brand is Volt, a servo-actuated gimbal that automates several of the trickier parts of operation. With a Steadicam’s sled bottom-heavy, traditional designs would hold a level horizon until walked around a corner. At this point, the operator becomes responsible for correcting the tendency for the bottom end to swing out and disturb the horizon. Volt deals with this automatically, as well as allowing for maintenance of any desired pitch angle. Doing that without a Trinity-style gimbal clamped to the top end is a new and useful idea.

Moving a camera smoothly through a scene is one thing; performing multiple takes with perfect repeatability is quite another. For a shot that needs to move a significant distance, a conventional robot arm just won’t do. A system such as Technodolly, offered in the UK by Sandstorm Films, does exactly that, and in a format that can reportedly deploy from a van in a couple of hours. Sandstorm’s set-up is a dolly-and-crane combination, capable of placing cameras up to 35kg anywhere, in what is essentially a cigar-shaped space.

Machines like Sandstorm’s Technodolly are unusual in that they’re robots designed to not behave like robots. It’s not unheard of for productions to use technology like this for no reason other than creating a smooth, perfectly feathered crane move. At the other end of the capability scale – if we’re interested in cooperation with different gear – the Technodolly has full integration with Unreal Engine and is likely to find employment on virtual production stages, or any situation where visual effects previsualisation is involved. At first glance, Technodolly looks like one of Supertechno’s cranes on a track, but it’s a lot more than that.

A call to arms

Manchester-based G6 MoCo’s more compact options include two robots: Stealth and Raptor. The former is the largest and most capable, carrying cameras up to 20kg through an operating volume up to four metres across, without even needing to be on a dolly. G6 publishes an accuracy spec for its robots quite prominently, and it’s interesting to note that the Stealth robot should repeat moves within just 0.04mm. Putting a number on these things sometimes makes it clear why this is such specialist work – and why the technology needs to be so finely made.

The Raptor arm is smaller, at a mere 60kg to the Stealth’s 255kg, achieving reach of 2.2m. Payloads up to 10kg are possible, and the company helpfully notes that the arm works very nicely with one of Vision Research’s Phantom high-speed cameras. Motion control isn’t the only arrow in G6’s quiver, though. Keen to cover as many bases as possible, the brand has a tracking vehicle with Steadicam, Motocrane, and is promoting virtual production facilities – of course, with one of those impressive motion-control robots taking pride of place.

Anyone who attended NAB Show back in April will have seen one of the incumbents of camera robotics right inside the doors of the main concourse. Mark Roberts Motion Control showed one of its impressively sprightly Bolt robot cranes integrated with a virtual production set-up. That didn’t test the incredible speed of which the robot arm is capable, having been designed to follow falling objects with high-frame-rate cameras. But it did demonstrate that the usefulness of much modern tech is increasingly dependent on the software driving it – and what it can talk to.

But it’s a mistake to think of Mark Roberts only in terms of motion-control robots for single-camera work. Given there are far more news and sports broadcasts in the world than high-end feature films, solutions like the Polymotion range – which provides software and hardware for automatic subject tracking and graphical integration – make a lot of sense. The Studiobot will be familiar in layout to anyone that’s laid eyes on Mark Roberts’ motion-control cranes, but it’s most often shown mounting a studio camera, tightly integrated into live broadcast systems.

In certain broadcast studios, cameras glide around as if operated by the Invisible Man – and that’s something Shotoku can help with. Long associated with the sort of camera robotics widely seen on news broadcasts, the company’s line features pan-and-tilt heads, pedestals and the SmartRail track system. This can operate either as a conventional floor track or mounted overhead, with the tower and camera suspended beneath.

Perhaps most impressively, the SmartPed pedestal has options to generate camera position data for AR or VR applications. This is achieved with reference tiles built into the studio floor – alongside the Absolute Navigation System, an optical motion tracker based on the Mo-Sys Startracker that’s increasingly visible in virtual production. The emergence of the FreeD IP protocol for tracking data also means that Shotoku’s support gear can potentially talk to other compatible equipment. Sports, game shows or current affairs can all take advantage of the many ways to drop virtual objects into broadcast studios.

Reach for the skies

Outside the studio – in fact, way outside the studio – there’s probably no bigger name in field camera support than DJI, thanks to the near universality of its Ronin gimbal. The Ronin 2 update brought improved handling of larger, more heavily accessorised cameras up to a little over 13kg, easier camera mounting and tuning, and other improvements besides. The company’s most recognisable recent release has been the Ronin 4D, which packs in cameras (including a full-frame option), four axes of stabilisation and lens control – including, amazingly, onboard laser-based autofocus, leveraging DJI’s own hyper-compact servo lens designs.

Whether or not we think of a drone as a camera-support robot (and we probably should), it’s hard to overlook what DJI has achieved in that field, too. The current darling is the DJI Mini 3 Pro, a diminutive alternative with a built-in camera on its own stabilised pan-and-tilt mount. While single-camera dramas might demand more sensor area than the Mini 3 Pro’s 1/1.3in chip, the sheer capability is mind-blowing given what helicopter-mounted set-ups might cost per hour.

Speaking of helicopters, consider the work of heavy-duty stabilisation specialist Shotover. The most prominent applications of its seriously upscale gimbals are regrettably difficult to see, as they’re generally hovering somewhere far overhead, strapped to an aircraft. The fact that some of its products are subject to ITAR – the International Traffic in Arms Regulations – demonstrates just how capable they can be, although the K1 aerial gimbal is designed to avoid that inconvenience.

There are more modest options – the G1 weighs less than 6kg, but sacrifices some axes of stabilisation and is only partly weatherproof. The company’s larger products weigh up to 80kg all-in, and have been employed to support six-camera arrays that capture vast background plates for effects-heavy blockbusters. Simultaneously, the company makes it clear that these gimbals are just as functional being carried by cars, boats and overworked grips, as they are on helicopters or fixed-wing aircrafts.

So, in 2022, there are choices for more or less any production to turn almost anything into a very worthwhile camera platform. It’s refreshing to see new ideas emerge, just as foundational classics like Steadicam refine new capabilities based on related fundamental technology. Crews on all sorts of projects are getting the best from both people and gear, in pursuit of that ever-elusive perfect move through the world.

First published in the July 2022 issue of Definition.