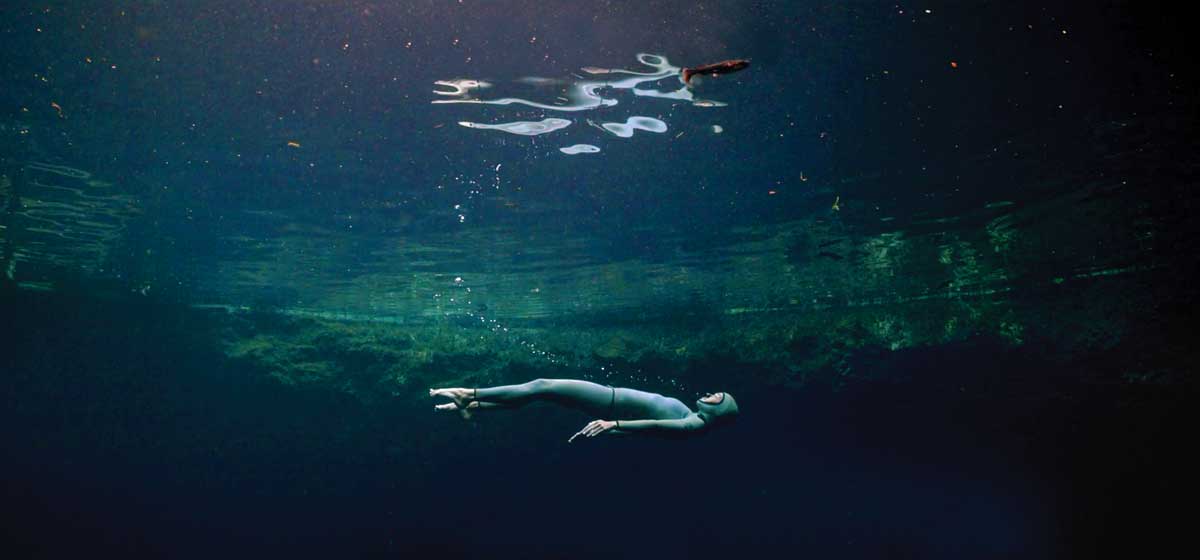

Part of that world: Lighting underwater

Posted on Oct 31, 2024 by Katie Kasperson

Part of that world

Underwater cinematographers and gaffers share insider tips for mastering lighting and colour accuracy in the depths

About two-thirds of the Earth’s surface is water, yet most stories are told on dry land. For filmmakers daring enough to brave the sea (or, in many cases, the swimming pool), the underwater world poses its fair share of obstacles – namely, that the laws of physics differ from those up above. When it comes time to light, there are a few tricks of the trade worth knowing; we hear from three underwater insiders on how it’s done, plus other challenges involved.

New rules

Water distorts light and consequently colour, leaving gaffers and DOPs with two choices when out at sea. They can either maintain authenticity by using ambient light – which can result in a desaturated image – or employ techniques like manipulating white balance, adding light sources and using filters to emulate their subjects’ true hues.

Underwater DOP Florian Fischer generally takes the latter approach. A founding member of creator community Behind the Mask, Fischer’s clientele spans luxury and lifestyle brands, tourism departments and travel agencies. He mostly makes documentaries and commercial content, working in ‘uncontrolled environments’ rather than studio builds or swimming pools.

“Nobody really knows how things should look underwater,” Fischer admits. “I think there’s a huge misconception, in underwater filming in general, that light brings colour. This is a problem.”

Under water, the quality of light can change metre to metre, the further you swim from the surface. Often, it’s a real-time guessing game when it comes to the camera’s white balance. “It’s not so easy to measure colour temperature under water – and do it precisely,” explains Fischer. He generally adds red tones in post-production to offset the ocean’s greyish blue.

Ian Seabrook (Wednesday, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice), also an underwater DOP, takes a slightly different approach. He uses a spectrometer in a custom waterproof housing to measure the spectral components of light. This helps him maintain colour accuracy whether shooting in a tank or in the wild.

Camera choice also comes into play, and Fischer always shoots in Raw format. He uses ARRI and RED cameras, which offer a 100,000 Kelvin colour spectrum – up from the standard 10,000 or 12,000. “That gives me the opportunity to skip white balancing in the water, which is super helpful. If there’s a cloud in front of the sun or you’re only changing a metre or two of depth, you’ll have a different colour spectrum. Manually working this out is difficult and often impractical.”

Fischer finds being ‘flexible and opportunistic’ is of greater importance, as the ocean – and the weather – is inherently unpredictable.

Swimming pools

Not all underwater filmmaking occurs outdoors. For big-budget franchises like Harry Potter or Mission Impossible, there’s often an on-set water tank – referred to as an ‘underwater stage’ – which can typically hold around 20 people at a time. “It’s a normal film set in many ways,” begins gaffer Aaron Keating, “but it’s submerged under water, with all the associated complications.”

Keating trained at Lee Lighting, with the Harry Potter films making up the bulk of his early career credits. He recalls his intrigue during Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, which features a lengthy lake scene – one of the Triwizard Tournament challenges and an integral plot point. Following that, Keating set his sights on becoming a commercial diver. “Focusing on that took priority over all other aspects of the industry. In time, it started paying off,” he states.

In those days, Keating and his crew used Kino Flo’s fluorescent tube lighting. “You had two settings – high or low – and it was one colour,” he recalls. “If you wanted a different colour, you had to break open the underwater housing and start again – a time-consuming process.” Now, modern LED technology makes underwater lighting much more efficient, enabling gaffers to make ‘last-second changes’ during shoots.

Working closely with the Underwater Lighting Company, Keating developed waterproof housings for Astera’s Titan and Helios Tubes. “They’ve definitely been a game changer – fully controllable underwater LEDs in every colour of the spectrum, plus all sorts of fancy effects.” They also have inherent safety benefits: “If there’s a blackout on-set, these lights remember their last order,” explains Keating. “They’ll stay on.”

Seabrook also opts for LEDs, using Creamsource’s ‘compact and powerful’ Vortex fixtures for surface illumination. “I have some preferred equipment, some of which I’ve used since I started shooting films,” he says, “in addition to new innovations, as lighting for cinema has evolved.”

He continues, “Lighting requirements vary from project to project. The set-up should be tailored to the specific needs of the shoot, be it narrative, documentary or advertising.” Seabrook touts Astera products as being “perfect for confined spaces,” while “traditional large sources such as 18K lamps are still used for daylight simulation.”

Many underwater filmmakers also use filters, typically to restore correct colours or – in outdoor shoots – match the ambient light spectrum. Fischer turns to KELDAN, a manufacturer of filters for lenses and light sources. “KELDAN have a unique system of filters for in front of the lens, but also in front of the light, ensuring that the colour temperature is consistent throughout the whole picture.”

Challenge accepted

Besides colour accuracy, there are plenty of other par-for-the-course challenges when working in water. Firstly, every submerged cast and crew member produces bubbles when breathing. “It’s one thing you definitely don’t have to deal with on land,” Keating points out. “You’ve got to watch that your bubbles aren’t getting in the way of any light coming through.” Rapid movements can also pose a problem, according to Keating: “It’s a constant game, being a bit of a lighting ninja,” and swimming without causing too much of a stir.

Outdoors, filmmakers are at the mercy of local weather conditions, which often change without warning. Seabrook stresses the importance of preparation – and considering logistics more generally. “What illumination is required and how will it be powered? Will there be a second vessel, separate from the camera boat?”

In a water tank, there’s also the issue of overcrowding. Certain people – like the talent, the camera operator, the gaffer and any safety personnel – need to be in the tank, while the director, producers and other crew members usually stay dry, observing from above. “Before you know it, you’ve got 20 people in one little area, all trying to stay out of each other’s way,” Keating shares, with this happening more often than not. “It’s important to keep things as lean and minimal as possible. Simplicity is key.”

Finally, underwater lighting (and filming altogether) requires a combination of water and electricity, introducing further risks – namely safety, but also kit failure. “When things go wrong, I’d say the biggest thing, which you address in prep, is getting things so dialled in that spares are ready to go straight away,” Keating states. “You completely minimise any hold-ups; you don’t want people waiting on you.”

One with the waves

Keating and Seabrook worked together on blockbusters like Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, and documentaries like The Rescue. “Being invited to photograph underwater sequences for Indiana Jones and be part of its legacy was a high honour,” Seabrook admits. During The Rescue, he swam alongside the cave divers who actually saved the trapped children in Tham Luang Nang Non. “Gaining theirs and the director’s trust was a truly fulfilling assignment.”

Keating has also worked opposite top talent, sharing the set with Tom Cruise on the Mission Impossible films. “There’s zero room for anything but your A game on a production like that,” states Keating. “I like the level of professionalism; that fine line between being on the ball and having a laugh where possible.”

Fischer’s recent credits include Netflix documentary The Deepest Breath, the story of a champion freediver, and a range of shorts for Behind the Mask, swimming alongside dolphins, crocodiles and killer whales. “We travel around the world,” he says, “and we try to speak for this group of people who make images underwater. We believe these people are ambassadors for the ocean; they take pictures in environments that most people can’t access without certifications, education and technical equipment. It all helps create awareness.”

Underwater filmmaking occupies its own production niche. It requires a unique skill set, whether in a studio or at sea. While distinct, both demand a love of water – or at least the grit to get wet.

This feature was first published in the November 2024 issue of Definition.