HDR: The future is now

Posted on Jan 15, 2021

With HDR being hailed by many as the biggest development in the world of production, we talk to the experts and creatives at every stage of its use to find out where we stand – and what the future holds.

Words Lee Renwick / pictures various

HDR has been an increasingly hot topic for a few years, but now it seems to be reaching a real fever pitch. Perhaps this is down to more recent advancements, or perhaps the slow yet inevitable takeover has finally crept up.

While it’s clear that HDR is a new and exciting opportunity, exactly what that opportunity consists of is a slightly cloudier issue for those not directly involved in the process. The high dynamic range element itself is easy to conceptualise, but in fact, it’s a much more complex topic than that, particularly in practice. It’s a technology that’s shaping every step of film production and, of course, the final viewer experience.

Each and every element of HDR has enough depth to fill countless white papers – and they’re certainly out there – so let’s consider the crucial elements. What is HDR beyond the basic concept? And how does it shape the production and post-production workflow, as well as the manufacturers providing the tools used?

Expert supervision

“First, what we need to understand is that HDR is all about display technology,” explains Pablo García Soriano, managing director and colour supervisor at Cromorama. “Even very early films stocks were able to capture a dynamic range of around 13 stops, but what we couldn’t achieve was a viewing environment in which we could display all of that latitude. We’re able to do that now because the contrast ratio of displays has expanded ridiculously. We’re now talking about contrast ratios of 1,000,000:1.”

Few other people in production have such an involvement in HDR. Across productions like Series 2 of His Dark Materials, Soriano manages the colour pipeline from prep and shoot to VFX, grade and DI. “The role has a big technical implementation, but also a big artistic element. The main role in the artistic side is to maintain the artistic intent in all the different viewing environments,” he says.

As an evolving technology, there’s some room for discussion on specifically how an image must be displayed to be considered HDR. For many, though, the gold standard is Dolby Vision, which necessitates a contrast ratio of 200,000:1 and a display brightness of 1000 nits.

While brightness can vary, the constant here is the contrast ratio. Brightness could be impossibly high, but if the darkest parts of the image are almost as bright as the brightest parts, that ratio is shot. Soriano tells us more.

“There are two ways of measuring dynamic range in terms of colours science: scene referred and display referred. The former is the input of light into a camera, measured in stops. The latter is what happens after, when this is transferred into a display-referred area, where dynamic range is measured in contrast ratio.

“When we’re talking about displays, viewing environment is extremely critical. The brightness of a Dolby Vision HDR projection in the cinema is only around 130 nits, but that’s because you’re in a very dark environment. If a cinema screen were 1000 nits, it would be unbearable. In colour science, there’s a branch that covers ‘perceptual engines’. These algorithms try to preserve creative intent, adapting the picture to different viewing environments. Providers like Dolby and Colorfront are working hard here.”

There’s another perceptual element at play in HDR, too, and it’s down to all of us. It seems an obvious point, but all viewing technology can only be related to the human eye. “There’s a concept known as 18% grey, often called mid grey. It’s what humans perceive to be the middle point between black and white, though it only reflects 18% of the light that hits it, not 50%,” Soriano explains.

“We see most of our information between 0% and 18% if we consider it in a measure of a camera’s stops, with each stop doubling the amount of light over the previous one. At base ISO, a camera behaves the same way as our brain, using around half the tonal data for that 0-18% range.

“The overall contrast ratio is just as much about those darkest parts as it is the brightest parts, and that’s where monitors are becoming much better. I’d also say most of the beauty of HDR is in those better blacks, too, and it all links to our evolutionary perception.”

Dynamic range is just one part of HDR displays, though. Another is colour space. “Light is two things: it’s intensity and chromaticity,” Soriano says. “With HDR, we also need to consider the third dimensionality of light, which is how colourful it can be.”

Much like the specifics of contrast ratio, what gamut and what percentage of it that needs to be covered vary. Dolby Vision requires a monitor that can cover almost the full Rec. 2020 colour space. Though this aspect of HDR has some catching up to do – and that’s if it ever gets there.

“The HDR television mastering is usually created for a 1000 nit display, but the Rec. 2020 colour space isn’t always used, simply because most consumer displays don’t even come close to that standard. With Rec. 2020, the top corner of that colour space triangle (at the luminance it should be) would essentially be a green laser. I consider no display will ever get there.”

“The vast majority of natural reflective colours are contained within the DCI-P3 gamut, you don’t need Rec. 2020 for those. Within the extra range of 2020, you’re talking only about a high-vis vest perhaps, or the fluorescent wings of a butterfly, or a lightsaber,” Soriano explains.

Certainly, there’s joy to be had from a wider gamut and the dynamic range, both for a viewer and those in all departments. “Viewed in HDR, a piece of paper may be 250 nits, while something that reflects 100% of the light would be at the display’s max – 1000 nits or higher. In SDR, those values might be 95 nits and 100 nits, so only a 5% difference. Thinking like that, you can easily see the separation that exists in HDR,” he says.

“So, who’s going to benefit most from HDR monitoring on set?” he continues. “The camera department will benefit, though HDR can be a little less forgiving than SDR, as much as it gives. Clipping, for example, will appear at the peak luminance of the monitor, which isn’t pleasant – and once that data is lost it’s hard to rebuild in post. More so than the camera, I’d say HDR benefits the art and makeup departments most. To see that wide separation in objects like clothing is significant and certain dark skin tones are actually outside the boundaries of the Rec. 709 gamut. Now you can finally see those textures and tonalities.”

He adds: “I’ve heard many directors say, after seeing an HDR pass, that they would have made a certain shot longer, because there’s so much more there than they thought. I’d say, eventually you’ll actually be able to read or visualise HDR moments within a script.”

On set

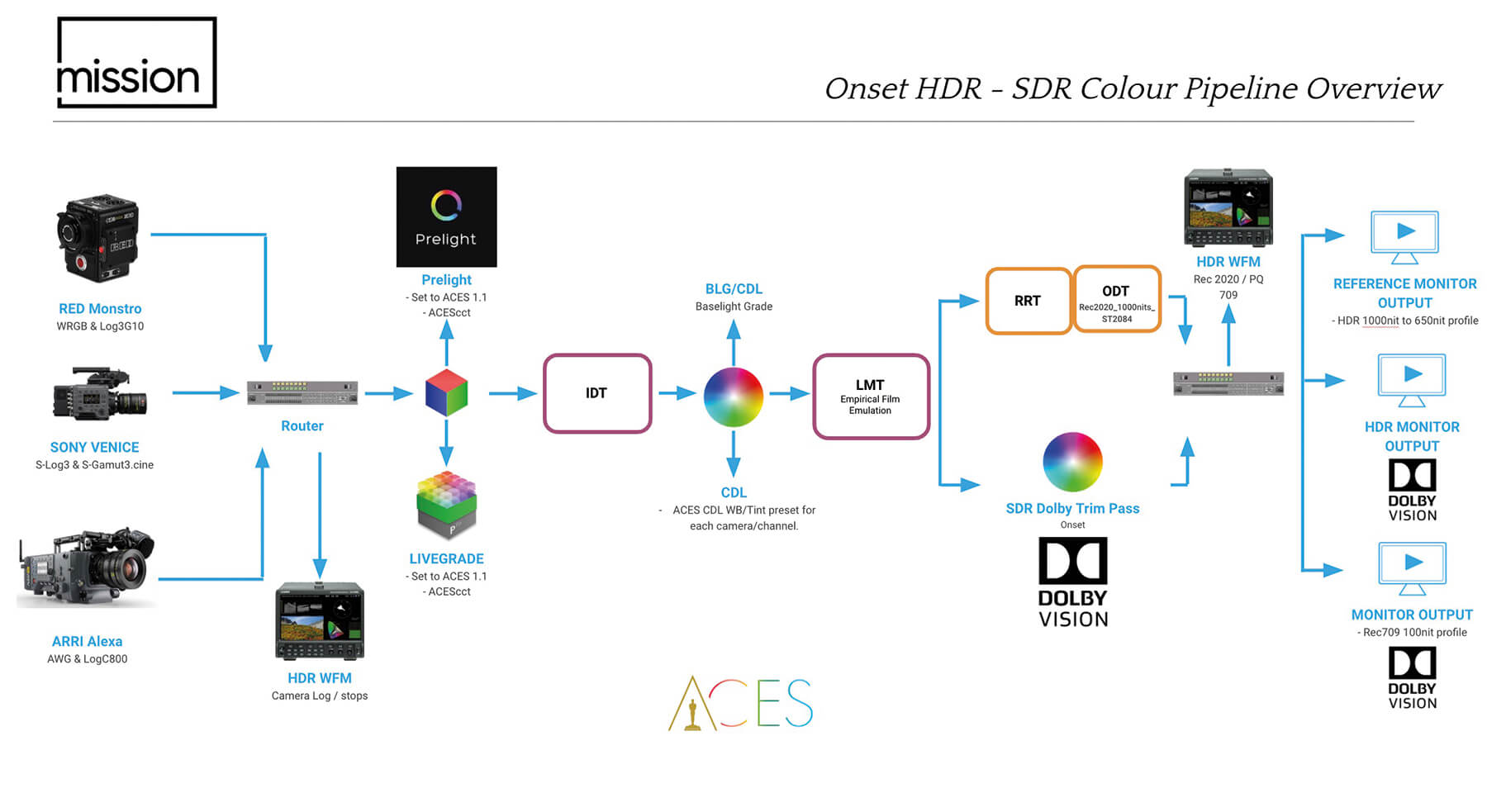

“A big part of that huge on-set change is with the role of the DIT,” Soriano points out. DITs just like Luke Williams, who works at Mission Digital. He explains: “It’s my job to make sure the digital negative is protected for HDR and SDR. This requires me and the cinematographer to monitor both outputs, as what would be clipped in SDR is present in HDR. It really is more important than ever to get the exposure right.

“We used the Sony Venice for the recent His Dark Materials Series 2 shoot, and the camera’s modern sensor, with 15 stops of dynamic range across 16-bit linear Raw files, makes that HDR exposure far easier. Another great factor is that it supports colour-managed workflows like ACES right out of the box.”

The Academy Colour Encoding System seeks to standardise the handling of colour through every stage of production. It’s a purely scene-referred workflow and assists in keeping the final product as close to the real, into-camera light sources as possible.

“HDR has given us a new set of brushes to paint our canvas with – which ones are used is up to the artist,” says Williams. “We can make images hyperreal or bring them closer than ever to what we’d see with the naked eye. It’s the flexibility that’s exciting.

“Working alongside David Higgs on His Dark Materials Series 2, we took full advantage of HDR. In the world of Cittàgazze, which has a bright, contrasty, Mediterranean feel, we were having to leave windows blown out in SDR, but in HDR we could maintain that feel and the additional detail. Yellows and browns, which were muted in Rec. 709, really came out more in the wider Rec. 2020 gamut, too.”

Williams continues: “In my mind, viewers have never had it so good. HDR formats like Dolby Vision are bringing dynamic deliverables that use HDR metadata to adjust to different viewing environments. What’s really great about this is, if you update your TV in the

future, you’ll actually see the same movie become visually better. I’d say it’s a much greater jump than when we went from SD to HD.”

Making the grade

Colour grading is another piece of the puzzle, with colourists like Toby Tomkins from Cheat having to adapt to – and reaping the rewards of – the new technology. Tomkins’ recently worked in HDR during the grading of Netflix’s I Am Not Okay With This.

“My creative approach is much the same in SDR and HDR, though there are certain nuances when it comes to tone mapping and gamut mapping that were never present, which does mean new tools and techniques,” he tells us.

“What it has given me is more creative options in deciding how I can elevate the images and stories I work with. Still, we must always ask if and when we should use the expanded range, and how that impacts the story we are trying to tell.”

Click the images to see a larger view

Soriano adds more about his own experience with colour grading: “There’s been a shift in the approach with grading. When HDR was first implemented, everybody was starting with the SDR grade then doing an HDR pass. Nowadays, I think it’s more often the opposite. What works in SDR doesn’t necessarily work in HDR, but what works in HDR will translate really well to SDR, simply because it’s always easier to destroy than to create.”

When we talk about the ripples these advancements have created reaching every element of the industry, it’s no exaggeration. To meet evolving needs, manufacturers are creating more powerful products than ever. Aside from the monitors themselves, this includes cameras like the Sony Venice, but post-production is reacting, too. The recent DaVinci Resolve 17 launch saw 300 new features added – notably, new HDR grading tools and primary controls. Blackmagic product expert, Simon Hall, tells us more.

“Manipulating highlights and shadows to the degree necessary in HDR can be challenging with traditional tools. DaVinci Resolve 17’s HDR palette gives a much greater level of creative control, with the ability to address the different tonal ranges of the image, from shadows and highlights to super blacks and specular whites.

“Elsewhere, there’s a new wider colour gamut, to match the capabilities of HDR monitors. It’s also great when you have a mixture of camera formats. When you drop varied media into the wide gamut, the controls work in exactly the same way, so you copy and paste a matching grade from one file to another. The viewer in DaVinci Resolve emulates HDR, but you’re not looking at an HDR display, so you need an output monitor,” Hall explains.

With HDR-capable software like this becoming more readily available to professionals outside the big-budget realm of high-end film and television, and cameras that can already capture the dynamic range necessary, perhaps in the not-too-distant future, HDR displays themselves will become just as accessible.

There’s much more to cover if a true deep dive into HDR is what you’re looking for, but for now at least, what it is and what it’s capable of is clear enough. It’s a world of creative potential, it’s a new viewing experience and, perhaps, it’s the very future of film and television.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of Definition.