Filming in Ryme City

Why does conventional wisdom demand that a film with digital characters has to be captured digitally? Pokémon Detective Pikachu blows that theory out of the water

Words Mike Elliot / Pictures Warner Bros / MPC

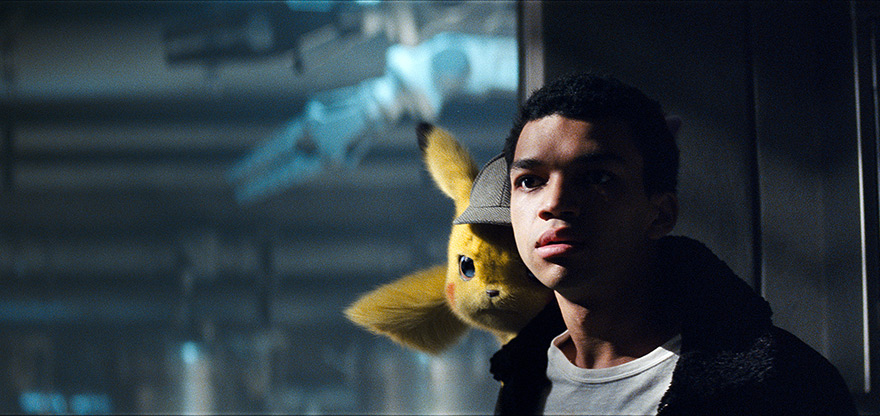

If you’re a new convert to Pokémon or still a fan from your childhood, it will only take a few seconds for you to believe the fantasy world that Pokémon Detective Pikachu presents to you. The VFX embedded in John Mathieson’s cinematography really is that good.

Mathieson is a true artist, but he wouldn’t thank you for calling him that. His skills are finely hewn from his early days on films like Gladiator and Hannibal, working with directors like Ridley Scott (he also shot Kingdom of Heaven and Robin Hood with Scott). He recently shot Mary Queen of Scots on digital, but thought there was a bigger movie to be made, perhaps with a bigger cinematic directorial vision.

He may or may not have his pick of interesting feature products, but a CG-heavy pre-teen origins tale might not have been on the top of his list. So, what made this movie rise above the others? Mathieson’s agent mentioned it to him, insisting: “It’s a great ‘fun film’ and tracks from kids to grandparents.” Mathieson adds: “I liked the director and he promised it would be stupid in this quirky Japanese way. There is a certain amount of honesty that comes through with this film. It doesn’t pretend to be morally superior or anything that it isn’t; this is purely a romp.”

Pokémon Detective Pikachu could be the start of a series of movies for the heavily invested among us. It had plenty of things going for it: Ryan Reynolds doing a de-tuned Deadpool for one, and a huge gallery of Pokémon characters to (literally) draw on for two. But cinema audiences can smell a rat when CG and the real world have a disconnect. The virtual world has to resemble the real world shortly after the lights go down or you’ve lost the mood.

“There is a certain amount of honesty that comes through with this film”

Location, location, location

When Mathieson came on-board, the director, Rob Letterman, promised him the use of film, less use of green screen and real locations – not just sound stages. This was music to his ears (and eyes). “Now, producers are so lazy, they want to shoot the outdoor scenes inside. It makes the budget so much simpler: if you have so many days on stages, you can work out that budget pretty quickly. If you have to go to a jungle in Thailand, for instance, or a desert beyond the Atlas Mountains and you have to build a road, stable some horses, dig for water and build a bridge, that all gets a bit tricky and there are a lot of unknowns. The laziness of studios who then say, ‘Just shove it against a green screen’ and it doesn’t match up,” Mathieson explains.

He continues: “You might not believe in Pikachu, but we based it on a place. Yes, it’s a CGI film, but our guy who’s two feet tall is in real places. It’s not based on someone in spandex floating on wires against a green screen. We didn’t do that: we went on to locations like Scotland where we got wet and cold. We built real places like bars with real coffee machines. Everything was real except for the guy in the foreground. But, as a percentage of the screen, the foreground is quite small. You’ve got real actors, real places, real surfaces and cars.”

Not only were the director and DOP sure that film was the right way to go, VFX supervisor Erik Nordby also announced a preference, which delighted Mathieson. He says: “All three of us argued with the studio for film and they let us do it as long as we didn’t go crazy on footage – and we didn’t. I think – you can ask the producer this – we saved money. When that film camera runs, everyone pays attention a bit more. With digital, even though you are very careful not to overrun, you always seem to shoot about an hour more a day of rushes than you used to. Rushes used to be around 50 minutes a day and that’s with multiple cameras.

“With digital, you are now watching maybe more than an hour more a day, so you end up watching it in the back of the car when you’re on your way home. There’s no connection anymore and you end up over-shooting to be sure you have the coverage. On Pikachu, we were a lot more frugal with our choices and managed to shoot around an hour and so didn’t go into overtime.” Mathieson admits many people have mentioned to him that the film looks great. He takes the praise and responds with the fact that it was shot on film with due care and attention. Wrongly, people assume that a movie with digital characters would feature digital capture. However, there is no reason one follows the other, and this film proves that. “We’ve got a juicy, rich-looking film. The LUT is in the film; it’s baked in. The colours are good, the neon has held up and the ‘noir detective’ element is there to see in the classic Raymond Chandler way,” Mathieson enthuses.

“You can almost sense Mathieson enjoying himself… the story allows him to layer the look through noir hard light”

Peeling the onion

Watching the film, you can almost sense Mathieson enjoying himself. This CG character detective story allows him to layer the look through the noir hard light with the shadows, enjoying the rich blacks that film allows, mixed with the eye-popping, crazy world of Pokémon.

Mathieson explains: “These are very colourful creatures in a very colourful world, so lots of neon in that Japanese style with no clipping, as we shot on film. Rob and I realised that we should be looking to find the look of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, so we tipped our hat to that movie, including the messy environment with all the garbage, mucky puddles and sleazy tone. It’s a bit edgy, not this pumped-up Pixar aesthetic, which it could have been if we had shot it all digitally. Film’s colours have more integrity, more variation, more subtleties and more hues than you do on digital.”

Mathieson is evangelical about film, as you can tell, and this movie and its look has given him a platform to explain a few things to media like Newsweek – not an everyday occurrence! He was asked to explain why the film looked so good, especially when the trailer for Sonic the Hedgehog came out looking flat and unusually clean. Mathieson again waved the film-look flag and mentioned in passing he had turned down Sonic, which was shot digitally. (Sonic’s release has been delayed until next February after a fan backlash against the eponymous character’s design.)

“We shot on film and I used smoke, light, reflections – I could burn things out. All those things are a bit of a no-no when it comes to digital. You can’t use smoke, you can’t burn stuff out, you can’t use intense colour. I was free to do it and delighted in the way it looked. Film is moving forward with the new scanning technology and matching well with it. A few years ago we couldn’t have made it look so good,” he says.

Embedded characters

We asked the VFX supervisor for Pokémon Detective Pikachu, Pete Dionne from MPC, how he managed to embed the CG characters so effectively into the movie. How did the performance capture for Pikachu and the other characters work? Director Rob Letterman’s brief for Pikachu’s facial performance was pretty simple: “Guys, I want to be able to read every single nuance of Ryan’s dramatic and comedic performance in Pikachu’s face. I also want him to look like the 2D anime Pikachu at all times. It also needs to look animalistic, because it’s not going to feel real if it animates like a cartoon face. And make him look as cute and appealing as possible.”

Dionne laughs: “It was quite a challenge to say the least! We began by building a facial rig system for Pikachu based on that of feline anatomy and structure, as this proved to be the closest animalistic equivalent to the anime Pikachu, based on his features and proportions. We explored tests early on with a facial rig that closer resembled Ryan Reynolds’s human face, but once the facial muscles started moving, it broke all realism and instantly appeared very cartoony.”

He continues: “Our next step was to capture a full Facial Action Coding System (FACS) facial workout for Ryan Reynolds, using a head-mounted camera and multiple additional witness cameras. This FACS workout is basically having Ryan striking every single facial pose and expression you can think of, including mouth shapes for speech, resulting in a library of around 80 facial shapes and expressions for us to match to. We then sourced a bunch of imagery from 2D animated manga to create a matching library of shapes to represent classic 2D Pikachu expressions, which essentially were variations of around seven key unique expressions, but all of them quite iconic and recognisable to Pikachu.”

The team then took Reynold’s expressions and 2D Pikachu’s expressions for all 80 target shapes, and created a new set of hybrid expressions within the constraints of the feline facial rig system they had built. This allowed them to directly map Reynold’s performance to Pikachu’s face, while staying true to Pikachu’s familiar design and feeling realistic from an anatomical point of view.

“During production, we captured all of Ryan’s performance and ADR with a head-mounted camera for facial capture, and this then served as the base for Pikachu’s facial performance, which the animators embellished over the top where needed,” Dionne adds. This development process took several months, but it was successful in achieving all the goals that Rob Letterman set in his initial brief.

A similar process was followed for Mewtwo as well, though he was a little more forgiving, due to having a facial structure that closer resembled that of a human. Other than Mr Mime, the VFX team didn’t attempt to leverage any direct performance capture for the remaining Pokémon. Instead, they looked to relevant reference and inspiration from the animal kingdom to try and inject a sense of realism into their animated performance.

Visualising the VFX

Definition also wanted to know which methods MPC used to help the live actors imagine the CG characters being there. Was there any AR help? John Mathieson mentioned that his dog substituted for Pikachu at one point!

Dionne recalls the work that went into helping the actors and crew: “It was very important to Rob that there was adequate representation of the Pokémon characters on set, both to help the crew visualise and anticipate where the CGI was going to go, as well as for the actors to perform against. To achieve this, we built and used a mix of stuffies, cut-outs and puppets for most of the characters. A typical set-up involved Rob blocking out the scene with the actors and crew using a puppeteered version of Pikachu. Once we were all ready to roll, we would leave the Pikachu puppet in the shot for the first few takes.”

When everyone was comfortable with Pikachu’s performance and the space he occupied, the team pulled him and the puppeteer out of the camera’s view for the remaining takes. “Once Rob had a take he was happy with, we shot a series of VFX passes. The first was clean plates and tiles of the scene with the actors removed, which allowed us to digitally remove the Pikachu puppet from the plate if Rob wanted to use an early take. Next, we would shoot a series of reference elements for our VFX lighters and compositors to match to. This involved standard chrome and grey spheres for lighting, but also material reference spheres that were built to match the same textures and material properties as our CG Pokémon – like yellow and brown furred spheres that matched Pikachu in colour and texture, yellow feathered spheres for Psyduck, rocky and leathery spheres for Torterra etc – for the majority of our characters. Shooting this for every relevant take gave us explicit reference for how these materials would respond in this environment, in these lighting conditions, shot on this film stock through these lenses, which removed a lot of the guess work when recreating it in CGI,” explains Dionne.

“Next, we shot 360° bracketed HDRI stills photography of the scene, with the camera positioned in the location of the CGI character. We used this to measure the position, intensity and colour temperature of the lighting in the scene, which allowed us to accurately reconstruct the exact lighting conditions in CG as they existed on set. It was a fairly involved process, but the team got very quick at executing it after each set-up, and the crew understood this was required to nail the integration between these plates and CGI characters,” he adds.

“Rob and John Mathieson’s decision to shoot Detective Pikachu on film was brilliant, and a gift to us in the visual effects team”

Virtual Production

Dionne goes on to explain why they moved away from virtual production for Pikachu, despite the growth of this new inclusive technology. “We explored various aspects of virtual production early on, but it became clear that it simply didn’t fit with the shooting style of this film. The main factor was Rob Letterman’s insistence to shoot as little green screen and sound stage material as possible, and to keep the photography rooted in real locations and sets as much as possible. Whether we were shooting on the streets of London or in the forests of the Scottish Highlands, we relied mainly on practical methods of representing the Pokémon in the scene, along with extensive pre-vis and tech-vis when relevant.” Dionne is effusive about his interaction with John Mathieson, as well as the unique look and experience that came with creating CG characters for a movie shot on film.

He says: “Rob and John Mathieson’s decision to shoot Pokémon Detective Pikachu on film was brilliant, and a gift to us in the visual effects team. The added cinematic quality and realism truly helped to ground our vibrant and cartoonish characters in the scene, in a way we would have probably struggled with more if we had shot clean, pin-sharp digital plates.

“In post-production, we fully embraced all of the qualities and nuances that both film and the anamorphic lenses provided us in the plates, and we went to great lengths to match this digitally. We mapped out all the lenses for lens distortion, chromatic aberration and vignetting. We recreated the exact properties and intensities of the grain for each film stock that was shot, and we created grade corrections to apply to our CGI to match the way the light rolled off in the shadows and highlights.”

Dionne concludes: “Though our raw CG renders of the characters and environments were quite clean and beautiful, the end result – once we crushed and stepped all over these renders to create the final integrated composite – left us with a very gritty and cinematic image. Which was exactly what Rob Letterman was after.”