Boys on film

Posted on Apr 13, 2021

The film vs digital debate is tired. It’s time to use old and new in harmony, maximising creative and practical potential. We speak to DOPs, Miles Ridgway and Spike Morris, about celluloid’s rise in short-form video

Words by Lee Renwick / pictures various

We’re 20 years on from the dawn of digital cinematography in mainstream feature film. Save for a few directors fighting to keep the old ways alive, it’s safe to say digital’s taken hold. On smaller projects, though, film never really went away – it even looks like there might be a resurgence on the cards.

In the worlds of music videos, television advertisements and beyond, spools are being loaded and cameras are whirring away. But why?

Quiet on set

The limiting factor with any production is money. So, it may seem like a strange choice for

smaller shoots, such as the music video for Arlo Parks’ Black Dog.

“It is an extra cost in relation to that budget,” agrees DOP, Miles Ridgway. “But that makes you more economic with your shooting. We only had three 400ft rolls for Black Dog. Each records about ten minutes, so that’s not much in total.

“It’s not that we’d have shot much more on digital – the project is still the project. There’s just an awareness that once it’s gone, it’s gone. We didn’t have playback with that small crew, either. In circumstances like that, when the camera starts rolling, everyone becomes intensely focused.”

He adds: “You also have to consider the similar costs when shooting digital. Large file storage isn’t free, and on projects with just a few rolls of film, like this one, that cost somewhat balances out. Film camera packages, like the Arri 416 I used, tend to be cheaper to rent.”

Without playback, ensuring you’ve captured a perfect shot is a real challenge, and certainly a daunting prospect to many. So, where does attention lie?

“It goes back to that added pressure and the heightened awareness that comes with it,” Ridgway says. “You must have faith in the skilled technicians on your set, but it certainly keeps you more decisive. It makes the results more interesting – at least in the sense that it’s organic.”

However, when there’s a monitor, it can be tempting to rely on it. “When there isn’t one, you just have to capture the moments you’re given. Shots are set up in the same way they always have been, but you don’t get to choose precisely how they look in quite the same way.”

In the Black Dog video, there are no telltale signs of celluloid, save for a few snippets. No strong grain, a subtle colour palette and reasonable sharpness. With much of the appeal of film lying in its look – in stark contrast to more modern offerings – this nuanced approach is interesting.

“We made the most of the subtleties 16mm offers, like the slight softness and halation”

Ridgway explains: “The Kodak 250D allows for that – we wanted to avoid an overdone look, so we didn’t underexpose and push process, and we didn’t shoot at wide open apertures. We still made the most of the subtleties 16mm offers, like the slight softness and halation you get with highlights. For us, that look was certainly part of the draw, but the philosophy and energy it brings to set really is an important factor.”

Commercial insight

In the world of commercial advertising, things are no less complex. There’s a lot to consider and, as with any aspect of filmmaking, there’s no correct answer.

“Every project requires its own unique tools,” confirms Spike Morris, a DOP who has worked on ad campaigns for the likes of Adidas, as well as creative music videos, including Moses Boyd’s Stranger Than Fiction. “I love the fast feedback loop of digital, with its ability to monitor and adapt, but celluloid is slower and more considered.

“Adverts are a strange one in terms of budget, because the money they make is so indirect. Some brands offer a set budget and ask for something that really represents them – something they can be proud of. That could be an extremely sharp set of product shots, but sometimes the softer, more organic – even abstract – approach of film is best.”

The lack of precise monitoring can also be a hard sell. It’s only natural for clients to want to see exactly how an image looks. “It comes down to weighing the many pros against that one con – and assuring them we are trusted professionals,” says Morris.

“I do agree that film allows you to capture results you ordinarily wouldn’t with monitoring, and

that focus is present in a way it isn’t elsewhere. I shot a documentary, Levante, with my Bolex H16 closed off in an underwater housing. We had no true idea of what we were getting, but the results were fantastic. That’s an extreme example of that process, but a successful one.”

All the visual benefits described by Ridgway are there for Morris, too, but there are more. “You tend to get fast frame rates elsewhere for these smooth, clean shots, but film is almost always 24fps. That traditional touch can take you back to what film originally was – a dream world.”

Considering the use of celluloid on short format and feature films, Morris adds: “There’s also a strong association to those Hollywood classics. Narrative film is similar at any length and the slower approach fits very nicely.”

It’s clear that this isn’t a ‘one or the other’ choice. Particularly in the world of short productions, film and digital are mutually beneficial tools.

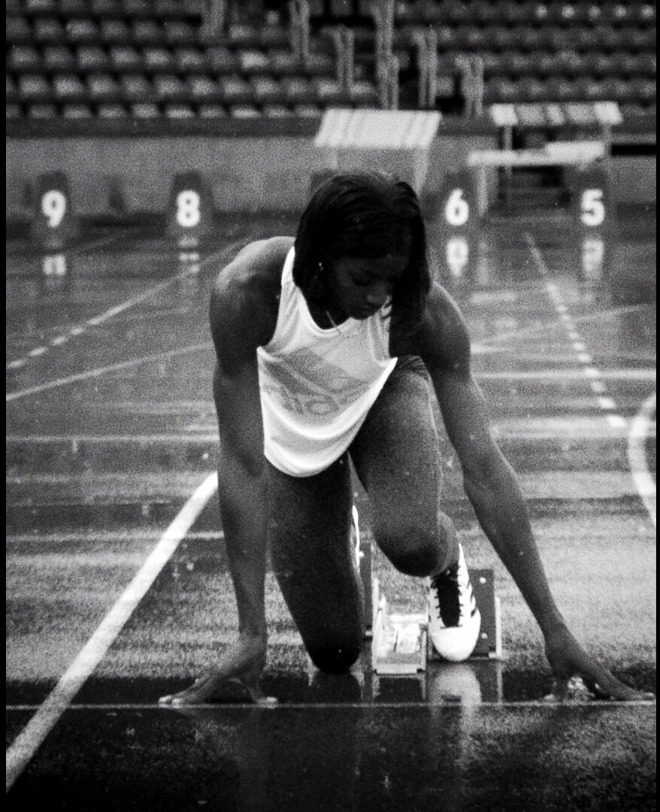

“We used a mix of footage in the Adidas Running commercial I shot. That’s a less narrative-driven approach, but for products like this, that mix is great for big energy and an eye-catching result. An eclectic look was the main focus, and this is one way of achieving that,” Morris says.

“There was some VFX work done on the Stranger Than Fiction video, but it was handled quite similarly to digital. When using film, you also try to capture some of these stranger effects in-camera. In this case, the blown-out look was because we painted our performers in reflective paint and overexposed massively. Again, though, we were only able to do that thanks to extensive testing on digital.”

So, with tools that could well be relics in a modern era, what’s the lasting draw, particularly outside the world of feature film? A distinctive look that tells a story? Certainly. Organic results that can sell an idea? Often. Perhaps what it all boils down to is very simple: more creative choice, using everything at our disposal, old and new.

Read this article in the latest issue of Definition to see more celluloid images, and to explore more of our content.