Acute controversy

Posted on Nov 10, 2020

Maïmouna Doucouré’s Cuties has been the subject of much attention since its release, for better or worse. We talk to DOP Yann Maritaud, to find out more about the unflinching approach to the film’s visuals.

Words Lee Renwick / pictures Netflix & Allociné

When Cuties hit the festival circuit earlier this year, reviews were overwhelmingly positive, with critics calling it “bold”, “evocative” and “culturally significant”, and Doucouré claimed a Directing Award at the Sundance Film Festival for her efforts.

In the months since, though, the film and its creators have been subject to a torrent of abuse as it found itself at the heart of a Twittersphere controversy.

Now, in stark contrast to critics’ reviews, ordinary viewers – or perhaps not viewers at all – have shown their disdain to the greatest possible degree. Cuties has a collective viewer rating of just 2.8/10 on IMDb and, if you Google the film, the top-voted tags include ‘disturbing’, ‘gross’ and ‘cringeworthy’.

The story follows Amy, a pre-teen Senegalese immigrant living in a devoutly Muslim household, daughter to a distant father and a downtrodden mother. At the time of her burgeoning adulthood, she meets a brash and energetic dance troupe made up of girls. Though they’re her own age, their cultural backgrounds couldn’t be further from Amy’s. And so, our lead finds herself with a choice: have the traditional role of women thrust upon her like her mother, or discover a new and radical type of womanhood with the help of her new friends.

Just mentioning ‘pre-teen’ and ‘womanhood’ together is enough to ring alarm bells for some – and so we find our controversy. Doubtless, these are difficult waters to navigate. Some argue that difficult real-world ideas like the sexualisation of young girls are impossible to explore fully in art without showing them as they truly are, while others argue that to do so is gratuitous and only serves to feed the issue.

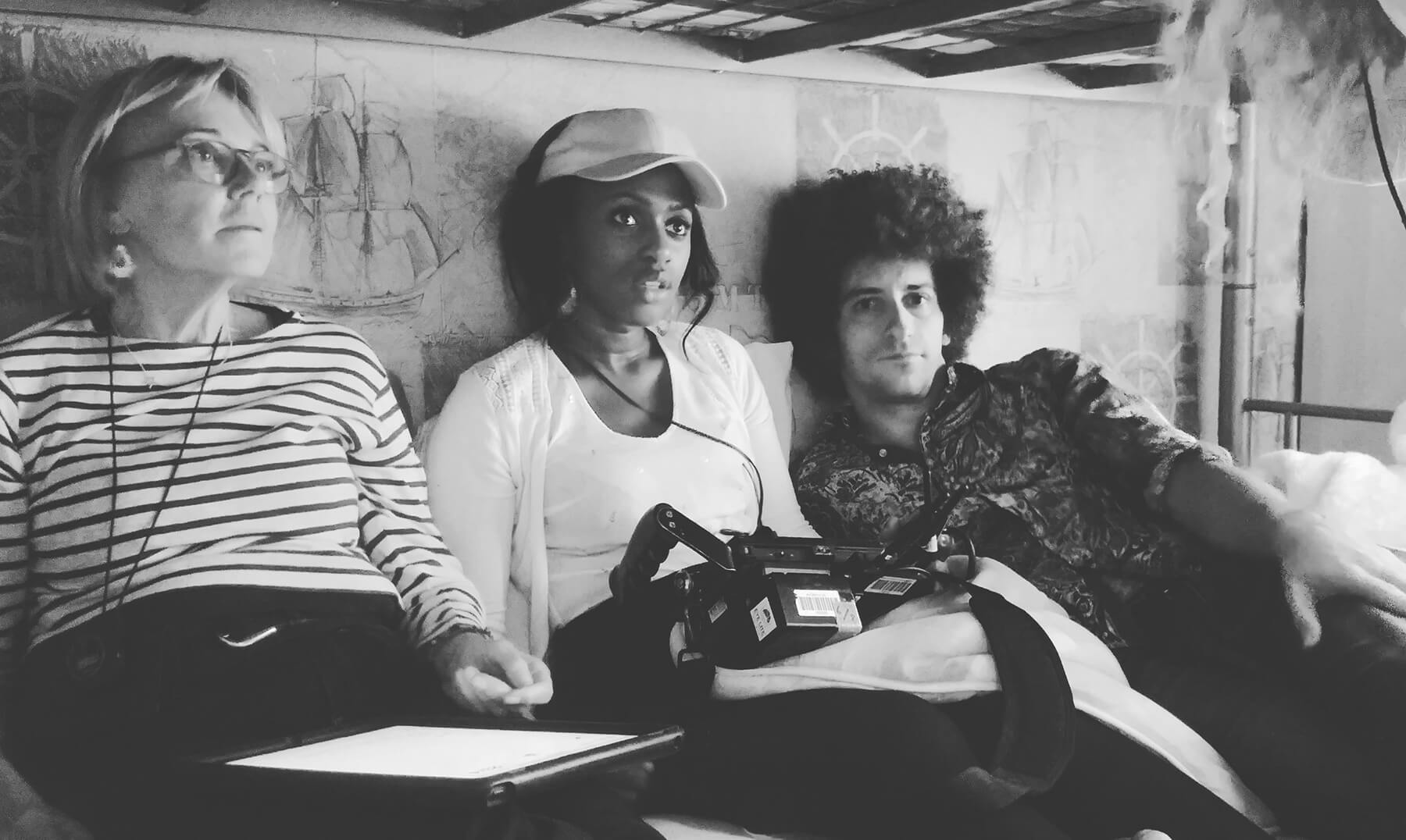

Having written the script with heavy influence drawn from her own experiences as a girl, Doucouré is as qualified as any to tackle the issue, and evidently, she opted for the direct approach. But, with outraged surface readings and huge degrees of reductivism surrounding the film, much of its nuance is lost. So perhaps, at least here, the more poignant question is not why the film was made in such a manner, but how. To find answers, we talked to the film’s director of photography, Yann Maritaud.

Up close and personal

Cuties is an extremely intimate film, thematically, but also visually. As Maritaud explains, these two elements were not at all disconnected. “From the earliest prep, one of the most important things for Maïmouna and me was to tell Amy’s story from her point of view. We worked hard not to have an adult eye on the story, but to have the viewer put themselves in the shoes of this pre-teenager for an hour and a half.”

It’s true, Amy is very rarely subject to an adult’s gaze – viewer not included. In line with this, we often find ourselves in unique frames. Early in the film, when Amy hides under her mother’s bed, for example. Here, we’re offered only an extreme close-up of Amy’s face and her point of view of her mother’s feet as she stifles tears down the phone. Throughout, the camerawork treads a fine line; we’re not aware of the camera in a direct sense, but there’s a pervading feeling of being very close to the bone.

“We wanted a very organic way of filming, staying as close to Amy’s feelings and emotions as possible,” Maritaud explains. “So, we decided to make the whole film with handheld camera, positioned at the height of the teenagers’ eyes. We wanted to show only the things that Amy can see or imagine.”

Where this takes us as viewers differs greatly from scene to scene. At times, we share a nostalgic childhood joy with the girls, but in others we intrude and trespass on moments we feel we simply shouldn’t see as adults. Despite the challenging feelings these latter scenes invoke, they were a critical part of the film’s exploration. Perhaps only in looking at the larger whole can we approve or disapprove.

“The camera never lets go of Amy’s viewpoint through her life experiences,” Maritaud says. “Some experiences are still very childish, and some push her too abruptly and prematurely into an adult posture that appears disturbing. It’s precisely by always keeping this same closeness that certain scenes, because of their content, are received very differently.

“Overall, for me, there was something instinctive in the way I shot the film – in choosing a point of view at the beginning and not letting go of it under any pretext.”

Taking a brief moment to address criticisms of the film, Maritaud deliberates. “My position is very clear: the purpose of these controversial scenes is to display how these little girls see themselves. The visuals in the film reflect the image the children intend to convey through social media and in front of their audience at the competition.

“Still, I am aware that we are dealing with very disturbing realities in our society, and that this is a very delicate and emotional subject.”

Shaping the look

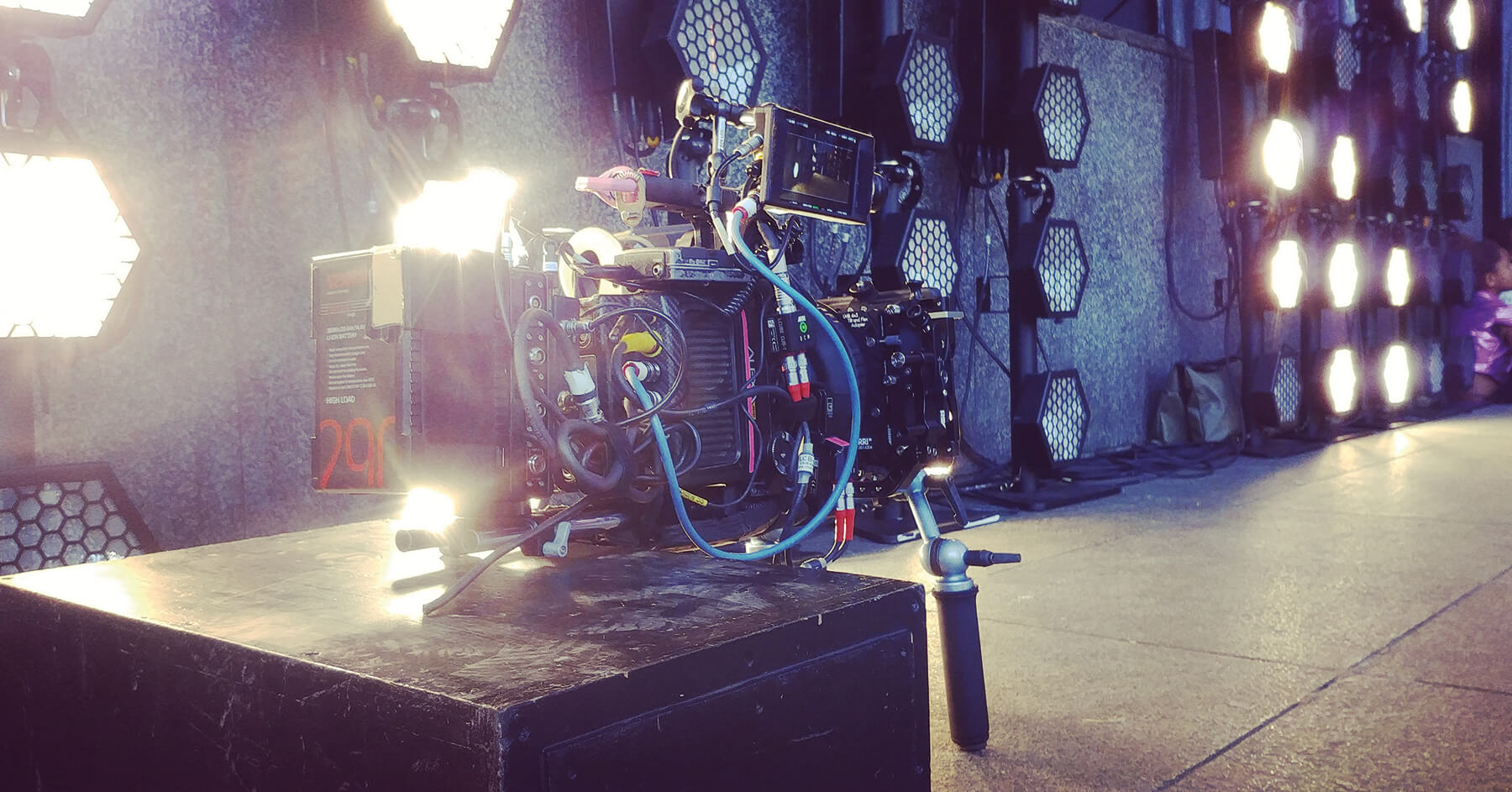

With Maritaud’s distinct vision in mind, next came the matter of finding the right kit for the job. “The choice of the camera was easy, because I knew that we were going to spend long hours every day with the camera on my shoulder to give Maïmouna the possibility to work on very long takes and improvisations with her actors,” he explains.

“I needed a lightweight and functional camera, but also something robust and reliable, so I chose the Alexa Mini. We often had to have the camera at hip height, so I found the LCD very handy, and it meant I could avoid adding too many accessories.”

When it came to lens selection, Maritaud opted for something altogether less modern. “I’m often very concerned when I’m shooting digitally that I must reduce the too-surgical, too-defined aspect of digital cameras, as it’s just not to my taste,” he says.

“In general, I find the oldest optics I can and I diffuse them even more with filters to achieve a more pleasant texture. In this case, we went for the Zeiss Super Speed Mark I lenses and a Mitchell Diffusion Filter. We tested at least ten different sets of lenses, but it was these

that caught our attention. Beyond their soft texture, they are optics that have a very particular rendering with triangular bokeh. This strange feeling distorts reality a little bit, and we found it added to a fairy-tale aspect of the film that we subtly introduced throughout.”

“There are two universes in this movie,” Maritaud explains, as conversation moves on to lighting. For the viewer, this much is clear. The two locations we watch Amy navigate – her home and the world outside of that – are representative of the two possible lives she may eventually lead.

“Amy goes out of her home environment to seek refuge, so the exteriors had to be bright and attractive. Though, with all the improvisation by the girls, we ended up with a 360° shooting axes, so I couldn’t do a lot of things. We relied on the light of the sun, then we shaped the look during colour grading.”

He continues: “In her home, I had to create a more oppressive atmosphere that closed in as the film progressed. With my gaffer, Cyril Bossard, we thought about lighting as much as possible from the outside so that the set would be a completely free playground for the actors. For this, we didn’t use anything too extravagant. We had some HMIs, like the Arri M40, which were bounced with large light boxes placed outside the building.”

Ultimately, what we’re left with is a complex work, bound to challenge and divide viewers. Inarguably, it’s intentional and unwavering in the message it carries.

Sharing his final thoughts on Cuties, Maritaud considers the end result. “I find the film well accomplished. We did it to raise awareness of an important subject of society, and in that, I think it’s successful,” he concludes.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Definition.