Why AVID Shouldn’t Be A Listed Company

Posted on Feb 12, 2015 by Julian Mitchell

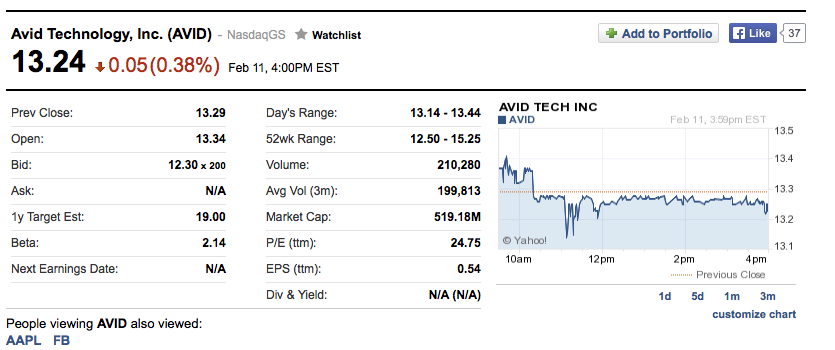

On the 24th of February, 2014, Avid received a letter from the NASDAQ Qualifications Hearing Panel stating that it had delisted Avid from the exchange and would suspend trading of its shares.

Avid had failed to submit timely financial statements – basically as it had discovered that it needed more time to restate some of its historical accounts – so they had expected to be delisted.

Avid have worked hard to rectify the issues, and NASDAQ trading in their shares restarted on the 8th of December. This fulfils an important duty to their shareholders and, as a long time user of their products, I wish them well.

However, I do have to ask why they ever floated on the NASDAQ in the first place. Stock exchanges have a nasty habit of being tails that wag dogs.

The basic problem is that people want to make money by trading in your shares, and that means that your share price must go (broadly) upwards – forever. For that to happen, your company has to grow – and continue growing ad infinitum – or your shareholders get grumpy.

That’s hard for most companies – even behemoths like Apple or Microsoft – but it’s well nigh impossible when you sell niche products into a niche market. Avid needs to constantly grow that market – which isn’t really possible on a grand scale with Pro Tools and Media Composer – hence their acquisitions policy and forays into consumer brands like Pinnacle.

Avid has another, historical, structural issue. They built their company at a time when video systems were very expensive, complex and bespoke. They required custom hardware – and therefore a hardware development team – and a worldwide network of dealers and service centres to support the customer base. Users were sold very expensive after-sales care packages to pay for this network, and the money rolled in.

Unfortunately, this business model is very easily disrupted by someone who enters the market with a software only product – taking advantage of the increase in the power of off-the-shelf hardware. They can sell the software comparatively cheaply and – most importantly – they do without the massive (and expensive) network of service engineers.

There will, of course, always be users who want the custom hardware and the support, but they are a niche within the niche – representing a shrinking of the market that your shareholders are pressuring you to grow.

It’s hard for Avid to adapt to compete with these manufacturers. Firstly, Avid has those core customers who want the advanced hardware and the local support office – and it’s a brave company that intentionally cuts off a core market. It’s even braver – and morally ambiguous at best – to fire all your hardware developers and support engineers and shut those expensive departments down.

And it’s not just Avid who suffer from this legacy business model. Whilst they rely less on custom hardware, VFX software vendors mostly built their businesses around the same time that Avid was building theirs – with similar business models. VFX software was complex, expensive, and came with yearly service contracts that often ran into the tens of thousands of dollars.

Autodesk and The Foundry have started to democratise their products – Smoke and Nuke – lowering prices and offering flexible subscription schemes, but one of their direct competitors – eyeon Fusion – is now free, following eyeon’s sale to Blackmagic Design. It may be a slightly restricted version of Fusion, but it’s really hard to compete with free.

Blackmagic famously did the same with DaVinci Resolve – the free product is very good and the full version is inexpensive. It has made it difficult in parts of the colour correction market. Avid have now entered this ‘freemium’ arena with a limited but free version of Pro Tools – one has to wonder if they will do the same with Media Composer. Will the VFX software vendors follow suit? As they say in Denmark – it’s dangerous to make predictions, especially about the future.