Survival saga: Society of the Snow

Posted on Jan 10, 2024 by Samara Husbands

Survival Saga: Society of the Snow

DOP Pedro Luque takes Nicola Foley through lensing Society of the Snow, Netflix’s breathtaking Andes flight disaster film

In October 1972, Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 crashed in the Andes mountains, leaving those aboard fighting for their lives in the brutal elements for 72 days.

The plane had been privately chartered by a rugby team bound for a reunion match in Santiago, but it never made it to its destination.

Instead, the young men and the friends they’d invited along were left starving and stranded, battling horrific injuries, freezing temperatures and scarce food supplies.

When rescuers eventually located the wreckage, they discovered that only 16 out of the 45 passengers and crew had survived the ordeal. They did so by resorting to the unthinkable: eating the remains of their fallen companions.

Miracle in the Andes

Over half a century on, the details of what unfolded during those ten harrowing weeks in the Andes still grip us.

It’s a narrative that’s proved irresistible to filmmakers – inspiring countless documentaries and cinematic adaptations – but that didn’t diminish Spanish director JA Bayona’s yen to make his own movie about the ‘miracle in the Andes’.

Bayona’s fascination with the story began more than a decade ago, when he chanced across Pablo Vierci’s book Society of The Snow during research for his film The Impossible.

Delving into the tragedy and its aftermath through intimate interviews with the survivors, the book served as starting point for his new Spanish language film, released on Netflix this month.

Bayona – known for horror-tinged disaster flicks – has a talent for grisly scenes and nail-biting suspense, but his goal in Society of the Snow was to explore the life-affirming themes of friendship and faith at the heart of the infamous Andes saga.

To that end, he dug beyond the sensationalist headlines, spending more than 100 hours with the crash survivors to lean on their first-hand experiences and portray the events in the most authentic way possible.

This sensitive approach to the subject matter was part of what drew in Uruguayan DOP Pedro Luque (responsible for the photography on Don’t Breathe, 2016, The Girl in the Spider’s Web, 2018, and Antebellum, 2020), who says he could barely believe his luck when he got the call from Bayona.

“He’s a great director who I already admired – and here he is talking about tackling this Uruguayan story, which is so important to my country. This is the stuff that forms the mythology around my nation”, he states. “It’s an important story for me, but it’s also one of the greatest survival tales in the history of the world. Yes, it’s been told a lot of times, but in my opinion it has never been told properly in a narrative piece.”

Unlike in other portrayals of the story, cannibalism isn’t the central focus. “It’s not what it’s about; it’s a story about friendship and how to give yourself to the group,” contemplates Luque. “This way, the story is more touching and more universal. It’s about how sometimes you’ve got to cross boundaries to survive; you have to adapt and change. It makes you wonder: what would I do in that situation?”

Freedom to Flow

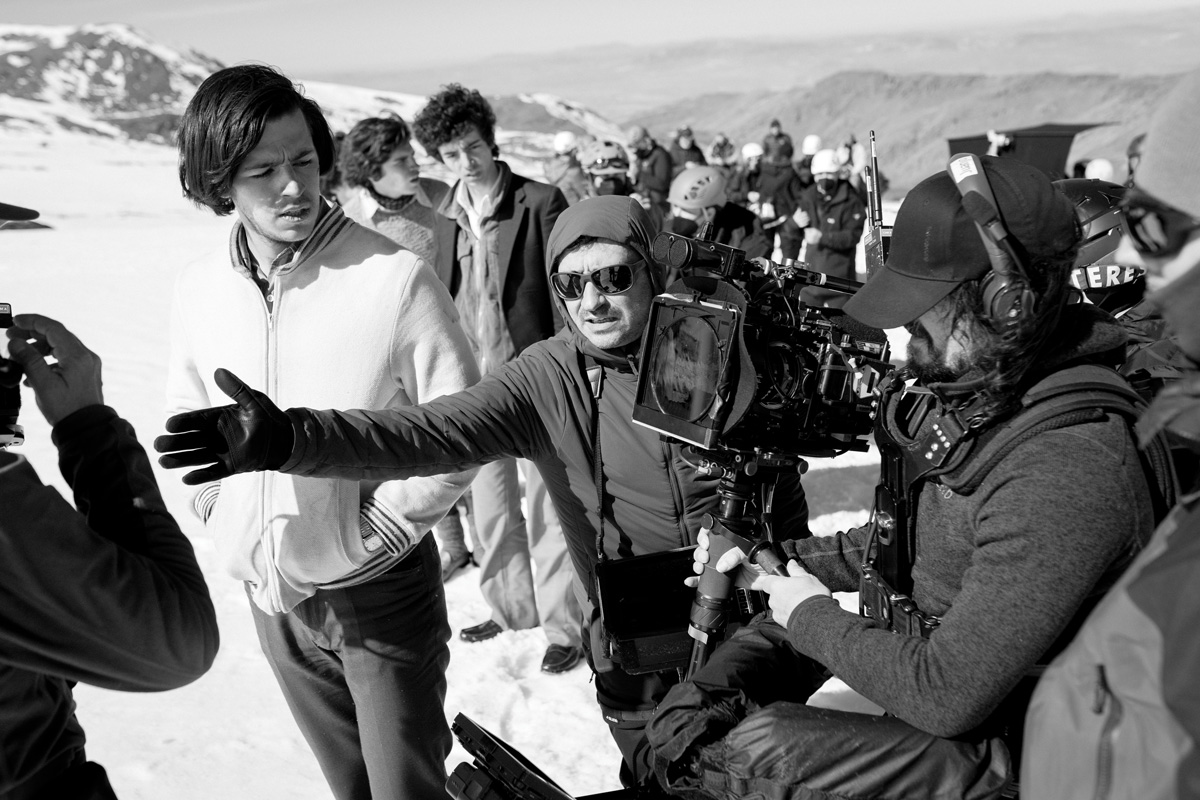

The film was exhaustively shot listed and storyboarded, but in the end Luque and Bayona erred away from a rigid approach, giving the actors room to improvise.

The plane wreckage was meticulously recreated (numerous times) and the cast rigorously rehearsed, but once all this was in place, they put the actors in frame and let things happen spontaneously – an approach the DOP describes as ‘freedom to flow’.

“The main guideline was to be ready for the actors and their emotions,” he shares. “Even though it was incredibly technically complex to shoot, we needed to have a team that was completely ready to respond to the actors, and the director’s desire for what we wanted to show in a particular moment.”

That demanded an excellent key grip and gaffer, skilled camera operators keyed into the action – and an almost documentary style of camera work in places, capturing the rawness of the actors’ feelings and creating, according to Luque, a blend of ‘realism and the poetry of cinema’.

“Even when we were on day 123 of shooting, we had to be sharp and alert. We had a good environment, good people and emotional comfort. I was crying in front of the monitor on some days and it was important for me not to be ashamed of that,” he recalls.

“The actors had spent around two months rehearsing, they were wet, cold and hungry, so we needed to be prepared and have the utmost respect for their craft – that meant being ready with the camera and making those shots count.”

A tale of three locations

The shoot was broken into three key phases; each a different destination posing its own unique challenges.

First was the site of the actual plane crash – the Valley of Tears – which the team visited three times ahead of principal photography, collecting as much information as possible about the geography and light conditions so that they could recreate it accurately when they moved on to their main shoot location in Granada.

There was plenty of work to be done – specialist mountaineers captured expedition footage, the team gathered background plates and establishing imagery from drones and helicopters, and a detailed photogrammetric map of the landscape was created.

But what Luque recalls most vividly from this stage of production is how he felt when he saw the valley for the first time.

“I had goosebumps, it felt like such a sacred place,” he reveals. “I remember kneeling down and asking permission for us to do it all, to do it in a respectful way and give us strength to do something that won’t hurt anyone. It was so silent, and there was this feeling of immense and overwhelming space.”

Thanks to intense previs work, the team knew how the valley looked and felt at any given hour of the day or night; but the next challenge was finding a stand-in location without the practical difficulties of shooting in the deepest Andes.

They searched all over the world, from the Alps to South America, eventually zeroing in on a Sierra Nevada ski resort as a good match thanks to its snowy scenery and harsh sunlight.

The material from the third stage – shot around Chile and Uruguay – introduces the actors and shows them returning home.

Production continued at Netflix’s studio in Madrid with the recreation of the crash, a visceral action sequence that shows off Bayona’s well-honed horror skills to full effect, before picture finishing was delivered by Deluxe Spain, with the grade, online and finish completed in DaVinci Resolve Studio.

Snow Business

Shooting in a ski resort in Spain wasn’t nearly as challenging as working in the Andes themselves, but it came with problems – starting with getting the cast and crew to the 3000m-high location of the main set, says Luque.

“We picked an area that looked wild and real, like the crash site, but it was difficult to access. It was about an hour’s gondola ride to the end of the ski station, and then we adapted snow tractors into people carriers to take people on from there. We’d drive for 45 minutes in the wilderness – dodging avalanches on these dangerous mountain roads.”

Sometimes it would be covered in snow on arrival, or inaccessible due to a storm. On one occasion, they arrived to see the whole site blanketed in Saharan dust: “We woke up and the mountains were latte brown!” he laughs.

To mitigate further disruptions, the Sierra Nevada site was divided into three sets, including a huge stage on top of the ski station which featured a replica plane fuselage, real snow on the ground and 140 ARRI SkyPanels as a ceiling.

They also installed a large LED volume displaying the second unit’s footage of the Andes, allowing for maximum authenticity and enabling the team to adjust the colour temperature, exposure and camera placement as desired.

To help ensure that the digital and physical elements blended together seamlessly, the team worked with Cinelab Film & Digital in London to transfer their captured footage to 35mm Kodak VISION3 250D film stock, which was then processed and scanned back to digital.

This photochemical process gave the whole thing a patina of grain that broke down the digital quality and lent a retro feel, befitting the film’s seventies setting.

The third set was a backlot down the mountain where the weather was milder, boasting a 300x300ft reproduction of the Valley of Tears made from scaffolding and foam.

It also featured another fuselage, this time supported by a hydraulic crane to enable movement.

Six types of artificial snow were utilised, but sometimes – especially for close-ups – only the real thing would do: “We’d bring in truckloads of snow from the mountain in a crazy fashion. The special effects guy – Pau Costa – was fantastic, and we also used a German company called Snow Business for the artificial stuff, who were really great,” enthuses Luque.

Despite the large budget (reportedly $65 million) and the filmmakers’ wealth of experience, the shoot provided ongoing lessons all round.

Altitude management was a crucial consideration, with the backlot at 1000m and the highest set at 3000m, while the constantly changing landscape meant they had their work cut out ensuring continuity.

The altitude, coupled with the remoteness of the locations, also posed a problem for data management, which Luque admits ended up being ‘a bit of a mess’.

“We were doing super long takes. Cards are expensive, and they fill up! We had a professional skier skiing down the mountain with the cards and then she’d be towed back up. There was a base camp down the mountain where we had people working 24 hours a day with the data, which worked great… but it was definitely intense!”

Gearing up for greatness

The production’s deep pockets allowed for an extensive kit-testing phase in the Italian Alps.

“We tested the Sony Venice, ARRI ALEXA, ALEXA Mini LF, 65 – we needed pixel count for Netflix and had to go large format. We tested RED, Leica lenses, ARRI lenses, Hawks, Panavision – I had my favourites and put together an edit for Bayona, which he watched without knowing which one was which. Fortunately for us, we came to the same conclusion on what equipment we liked,” reports Luque.

The main package selected was an ARRI ALEXA Mini LF with Panavision T Series anamorphics, lending a classic cinematic look which the DOP and director both loved, but they also utilised GoPros, a RED Dragon, 15mm ZEISS Supreme Prime, Panavision Primos, various anamorphic zooms and an ARRI ALEXA for helicopter shots.

“It was luxurious – this was a big project, and we got a lot of cameras and lenses supplied. But they were all needed. We had a unit that would go to the top of the mountain when the weather was bad, and these two guys would ski up the mountain, set up camp and shoot. But at the same time, there would be a second unit that was doing stunts and they’d need two or three cameras, and we ourselves would need a couple of cameras for whatever we were doing, so we used them all.”

They also used Botlink’s Octocopter drone – which struggled in the altitude but ultimately delivered – breaking a record for flying a drone in the Andes in the process.

On the lighting front, Luque says he was on a mission to find the harshest lights he could. “I wanted the shadows as sharp as possible; when you are in the mountains, there’s less oxygen – less air between you and space – and the light is harder. You don’t get dust in the atmosphere that diffuses the light. We tested several solutions but opted for LED fresnels for the effect we wanted.”

For the interior shots of the cramped fuselage, Luque felt a more realistic look was achieved by lighting through the windows.

“It ended up being a matter of how to block an actor so he got a nice bit of backlight or chiaroscuro – we tested an LED roof but it looked super fake. The same thing happened outside on the mountains; we brought out lighting and some little inserts and stuff, but in general, it was about not touching it.

“It was about finding a good angle,” he continues. “Adding some negative fill here and there to get contrast. The cinematography had to be imperfect to make it feel more real. I understand we must have a certain standard, but when I see something too perfect, I disconnect from a story. Audiences feel the same.”

A healing journey

The meticulous work paid off, resulting in a stunning film that’s already wowed on the festival circuit and earned itself Spain’s nomination for best international feature film at the upcoming Academy Awards.

Luque feels his biggest achievement has been communicating the story so authentically and capturing the emotions of the actors on screen. “It was a big leap of faith for me, but I’m so proud of it – especially the ending.

“I’m so proud of the crew, too. They put so much of themselves into the work. We did a screening for all of the survivors and their families. In their words, they said they all finally understood what happened. It was healing for them.”

Society of the Snow is available to stream on Netflix from 4 January.

This article was first published in the January 2024 issue of Definition.