Fallout

Posted on Jul 16, 2024 by Samara Husbands

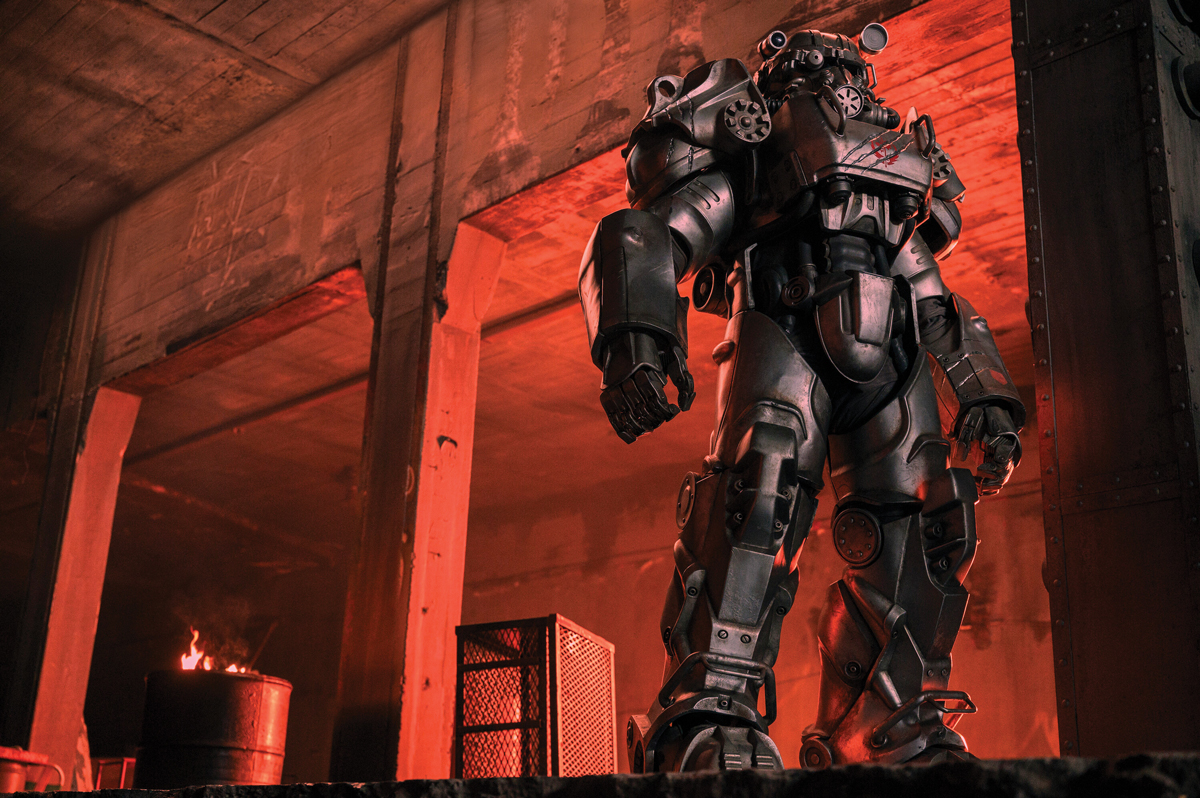

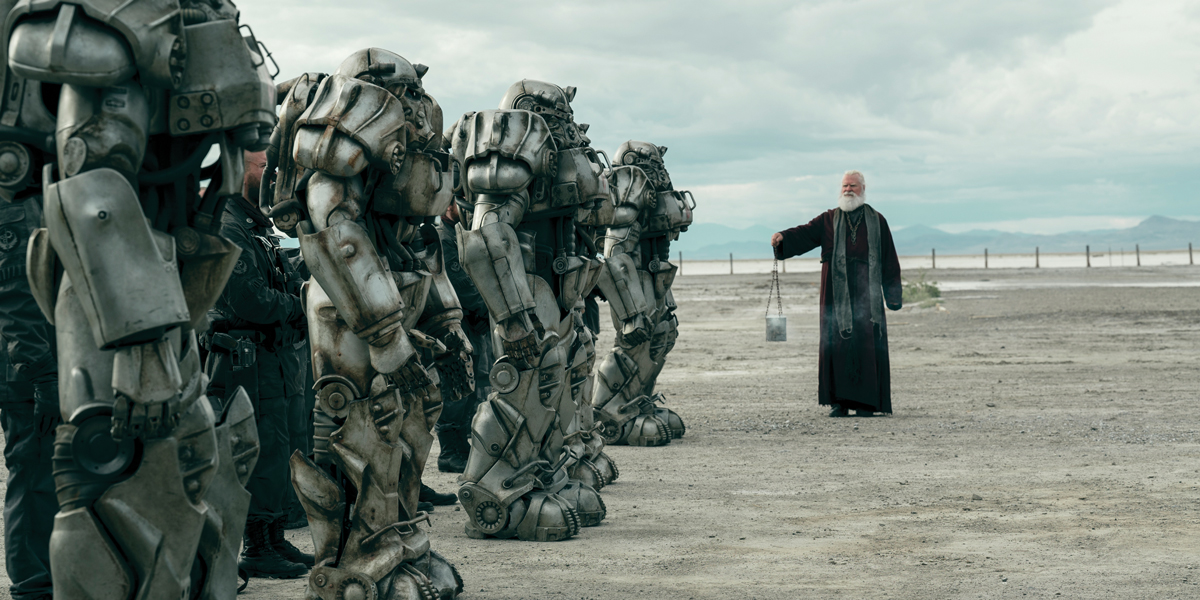

Lore & Disorder

Fallout’s speculative future called for a host of spectacular environments. Phil Rhodes discovers how cutting-edge virtual production techniques played a vital part

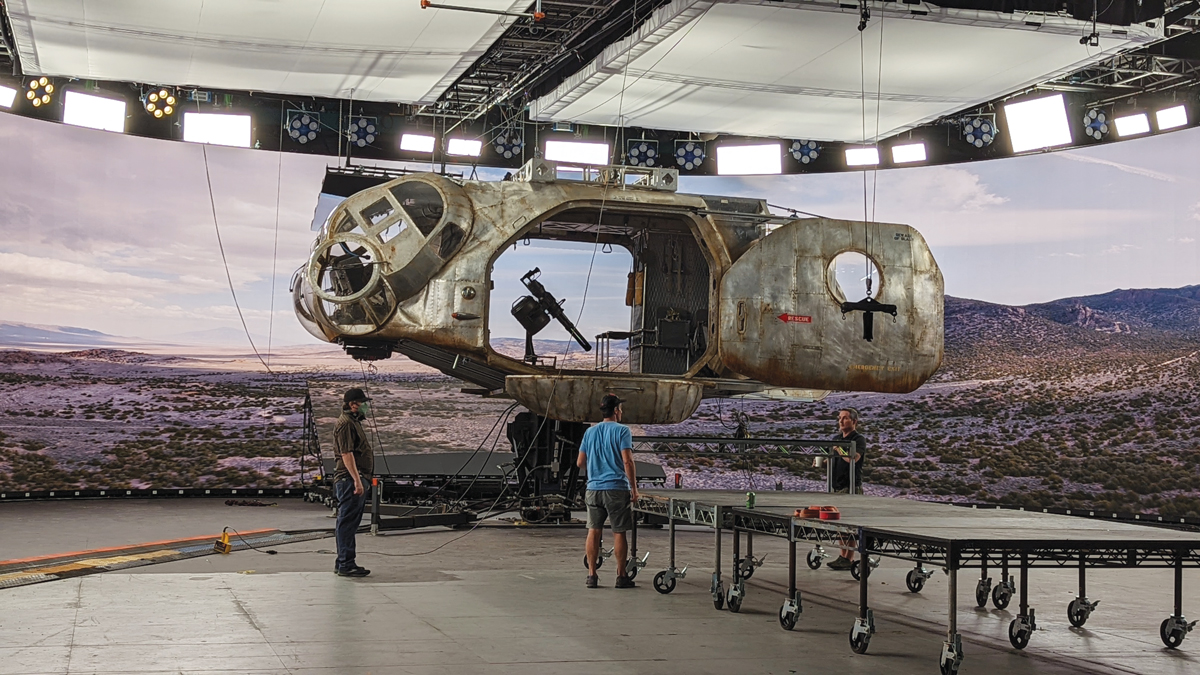

As virtual production has become a better-understood part of filmmaking, the vast set-ups which sparked so much early interest are often less common than facilities sized for cars and interviews. But Amazon’s production of Fallout needed some elbow room. LA-based studio Magnopus helped build a stage with enough space to do the job – and to suit the production’s ambitions to shoot 35mm film.

Magnopus’ director of VP, AJ Sciutto, had already worked with Kilter Films on Season 4 of Westworld. His involvement first began when the series was still in development, “when only the pilot had been written,” he recalls. “Creatively, we offered some guidance on the best use of VP, then worked with the filmmakers to analyse the scripts, so we could identify scenes and environments which would gain the most from in-camera visual effects,” he elaborates.

The stage built for Fallout would have a hybrid layout, with curved and straight sections, measuring 75x100ft overall. “It combined the lighting benefits of a curved volume with the flexibility of flat wall sections for longer walk-and-talk scenes,” Sciutto points out. As plenty of nascent facilities have found throughout the history of filmmaking, a building with uninterrupted space would be a concern. “Finding a suitable stage near the Brooklyn base of the production was a challenge, though we ultimately built the volume in Bethpage, Long Island,” he says.

Fallout’s LED wall was built using ROE Black Pearl 2V2 panels, controlled by Brompton Tessera SX40 processors. “For tracking,” Sciutto adds, “we used the Stype RedSpy cameras and the Stype Follower system for objects.” The facility’s servers, meanwhile, are packaged up in a shipping container, built out by Fuse to provide 12 4K outputs to drive the LED wall, and another six for wild walls to be positioned for specific set-ups.

“It’s all operated by six operator stations in mission control,” Sciutto continues. “From our team, 37 people worked on Fallout over the full season. We had 19 artists building virtual sets, six operators running the Unreal nDisplay system – with others handling camera tracking, lighting programming and overall production supervision.”

With the technical set-up in place, Sciutto and his team could move on to design. The economics of VP have always worked best on shows which might otherwise have relied on upscale set builds, as it was on Fallout. “We collaborated closely with production designer Howard Cummings and his art directors to determine what would be built physically versus virtually. With the scale of the environments, replacing those with physical set builds would have required massive stages or locations,” Sciutto highlights.

35mm had largely petered out in the 2010s, but Fallout is part of something of a revival. The intersection of 35mm film and VP, however, has been reasonably rare – though Sciutto immediately understood the method. “It brought a distinctive aesthetic, an artistic grit and a layer of separation between the different elements of the wasteland. But it also presented technical challenges, such as syncing the film camera with the digital LED walls and ensuring colour consistency between physical and virtual elements.” Fallout was shot on ARRICAM ST, genlocked to the video wall systems, but matching colour between the real and virtual worlds took deeper thinking.

Colour in VP is often an iterative process, but on 35mm that would be slower. “Part of commissioning an LED volume is ensuring a validated colour pipeline,” Sciutto explains. “You start with the source content in Unreal, route it through the various equipment and display technologies, then finish with the captured imagery in-camera. The process of developing the film captured on our pre-light days created a three-day turnaround from shoot to review. The video tap on a film camera is meant for framing – not colour accuracy – so we used secondary digital camera systems, allowing our operators to have accurate data to dial against.”

Sciutto and his group also worked closely with Fallout’s lighting team on an image-based lighting set-up capable of reacting convincingly to alterations in the virtual world. “It allowed us to dynamically change the lighting in real time, such as during a scene where lights needed to turn on while Lucy was exiting an elevator in the vault door environment. That on-the-fly adjustment wouldn’t be possible without a synchronised lighting system.”

The speculative future of Fallout called for a variety of spectacular environments, one of which depicted an ersatz virtual environment system purportedly created with fifties tech. Built to give the dwellers of an underground refuge the impression of open skies, the system would project images of the natural world as a background to a subterranean field full of real crops.

Sciutto describes it as ‘the wedding scene in the cornfield within Vault 33’. He adds: “The scene required a dynamic lighting change mid-shot, transitioning from dusk to nighttime, which was initiated by a narrative line from the Overseer.

“Since we had two existing lighting set-ups – one for sunset and one for night – it was as easy as animating the moon asset to rise while transitioning between the two lighting environments,” Sciutto reveals. “It was a great example of how VP can allow that kind of real-time environmental change.”

Different techniques were called for when the projection system was required to fail during a scene Sciutto calls ‘the battle between Vault 33 and the surface dwellers’. “We incorporated a film-burn effect on the LED walls when the projectors were hit by gunfire. Our Houdini team built this effect based on research into the burning patterns of fifties film stock,” he explains.

VP displays often have huge overall resolution, and Sciutto’s team had to build the necessary assets with that in mind. “Creating this imagery to spread across a dozen 4K outputs simultaneously through Unreal was challenging,” he recalls, “but with proper scene optimisation and updated EXR playback systems in Unreal, we created something visually stunning. Seeing this effect spread dynamically across the walls and affect the lighting of the physical set with orange light from the burning film added a lot to the intensity of the scene.”

With Fallout enjoying a glowing reception from both audiences and critics, a second season is reportedly in the works. As so often, Sciutto isn’t in a position to hint at Magnopus’ future projects – but as VP settles into position as a mainstream production technique, new ideas continue to flow.

The design and approval process is one place Sciutto sees opportunity for improvement. “We’re excited about WebGL and how it will allow filmmakers to enter their virtual environments as part of the development process, without needing technical assistance to deploy high-powered PCs and VR headsets.” That way, Sciutto goes on, the same assets might find new uses outside of production work. “The most interesting trait of web-based tools for 3D environment reviews is that the same technology can put audiences inside those finished environments once the show is completed and released.”

There’s a certain symmetry to the idea of a television show based on a video game that might, in the end, donate its assets back to a real-time interactive experience.

See inside the unique workflow behind the production of Fallout.

This feature was first published in the August 2024 issue of Definition.