3D scanning techniques for virtual production workflows

Posted on Jul 23, 2025 by Admin

“This technology will transform how live action productions can be conceived and planned”

New mobile 3D scanning techniques can help cinematographers drive new virtual production workflows from the ground up, discovers Adrian Pennington

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) has been used in heavy industries like construction and surveying for years, but has been too cumbersome and expensive for most film. Now, compact, handheld, cheaper devices designed to capture real-world locations as interactive 3D environments present a bold evolution in the cinematographic toolkit.

Aside from top-end models from Leica Geosystems designed for industry, lighter and less expensive scanners offering marker-free tracking include the Eagle from 3DMakerpro and the xGrids LixelKity K1 scanner.

The latter is particularly interesting given its compatibility with Jetset, an iOS app from Lightcraft that fuses CGI and live action in real time. Roberto Schaefer, ASC, AIC – who shot Monster’s Ball and was also the Bafta-nominated cinematographer for Finding Neverland – trialled the combination as a test for a short film under development for a director in LA.

“I discovered Jetset a year ago, and it was Lightcraft founder Eliot Mack who suggested I try it out with the K1,” Schaefer says. “At the same time, I had a project to shoot in Italy, so I decided to tie the lot together and fly out to Rome.”

The user’s smartphone can be attached to the K1 for real-time monitoring during the scan via a companion LixelGO app. The phone is used as a control module and viewing screen. The K1 itself has four cameras: two panoramic vision modules at 48 megapixels and two depth cameras.

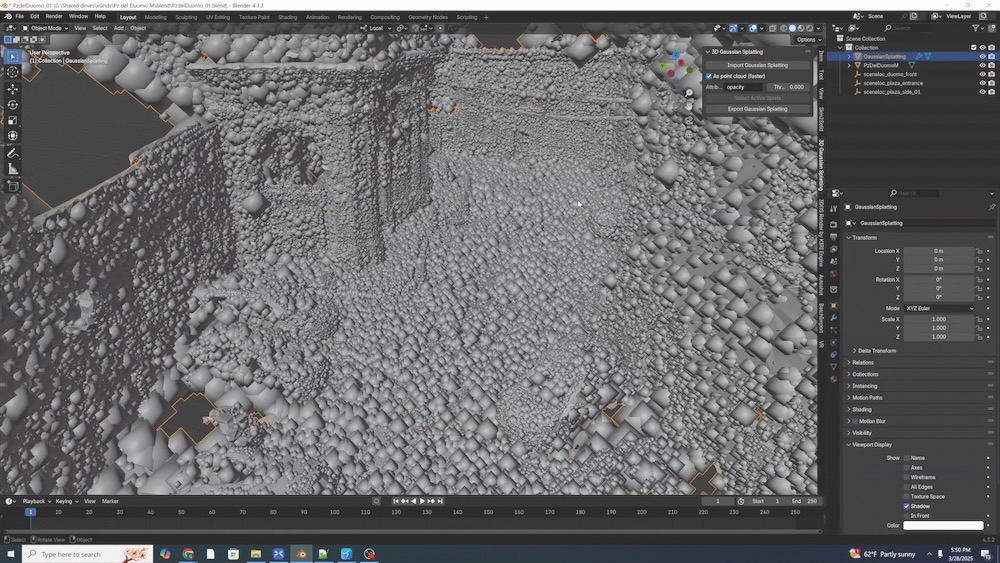

According to Bella Wan of xGrids, “The K1 scans primarily capture raw LiDAR point clouds and aligned image data. A computational process called simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) is applied and then the LCC Studio software generates the 3D Gaussian splat models. These final models with natural parallax, spatial depth and RGB colour can then be exported for use in other industrial software like Jetset.”

According to Schaefer, it’s a more efficient and agile form of photogrammetry which, while producing ‘extremely high resolutions’, essentially stitches thousands of stills together in a process that can be more consuming than simply walking around with a handheld scanner.

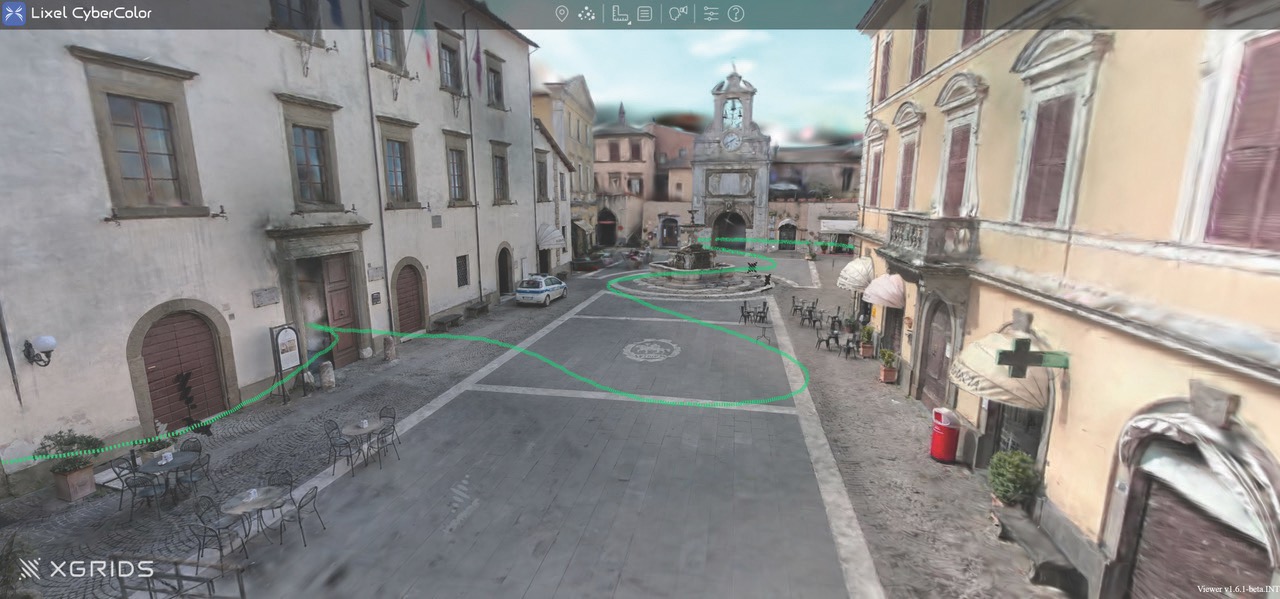

In Italy, Schaefer spent a day in Sutri, north of Rome, scanning buildings and streets previously identified by his director. “I shot a music video there with Belinda Carlisle many years ago, so I knew the town well. It has a beautiful piazza and churches, and it seemed like the right place. You have to walk in a zig-zag pattern for the scan to work, but you can see where you’ve been thanks to a green dotted line in the display,” he says.

Schaefer also captured some scans of Rome, including of the Colosseum, before heading back to LA. Having sent the raw data to Lightcraft over Wi-Fi, the scans were processed as files called Lixel CyberColor (LCC) ready for Schaefer to look at as soon as he landed.

“xGrids has a [Mac/PC] viewing application called LCC Viewer that lets the user navigate through an xGrids scan with a traditional keyboard and mouse. You can freeze frame, move within it, point to the ceiling (or sky), go left and right, or create stills from it.”

With the scans exported to Jetset, a director or DOP can test shot composition with a precise simulation of a specific production camera and lens, as well as real-time tracking of the camera’s motion.

“For example, they could load in the xGrids scan of Rome into Jetset, select a simulated camera and lens combination of an ALEXA 35 shooting at a 2:1 aspect ratio with a 32mm lens, and simply walk around their living room,” shares Mack. “Jetset will accurately track their motions inside the xGrids scan and show them what the view would be if they were standing in that exact portion of Rome (for example), holding that ALEXA camera and 32mm lens.”

Schaefer showed the results to his director. “He didn’t know what to expect, but he was surprised at how much we could explore and in such detail. He understood instinctively that he could plan an entire movie, including blocking and camera placements, remotely.

“You can measure things like doorways accurately to within two centimetres. That means you know in advance if a piece of furniture or a dolly can fit through this doorway, or how tall the ceiling is. It gives you a lot of options in your production office before you get to location.”

Schaefer says he’d like to see location scouts equipped with such scanners. “A location scout will often come back with hundreds of pictures of different places, which can be confusing to look at. Also, they tend to shoot with super wide-angle lenses, so even a small bathroom closet feels like it’s the Taj Mahal.

“When you’re done, you have a reference for every set and location on how it was dressed and lit. You can archive it, and if you ever need to do pickups, add close-ups or extend a scene in the same environment, you already have the entire set pre-built. You can then place it on a green-screen stage or in a volume. The scans are often high enough resolution – and even if not, the background walls in a volume are usually slightly out of focus anyway. It’s more than good enough for pickups.”

He thinks it’s a tool the whole production can use. “I would bring in the production designer, the costume designer, all the heads of department and especially the grips, key grip and gaffer. You can point out the size of a wall to the production designer or set decorator, so they understand how to dress the space. You could even display the output inside a VR application and have someone explore it wearing goggles – though it can feel a little strange. For example, if you’re in Grand Central Station or a massive concert hall, you would need enough physical space around you to walk the entire length of it in virtual reality because it’s so accurate – one metre in VR equals one metre in the real world.”

Schaefer suggests the K1/Jetset workflow could be integrated with an Artemis Prime viewfinder, allowing him to use a virtual camera with different lenses to previs, block and test camera positions and lens choices for an entire show using the scans. Among other benefits, this could help avoid costly on-location errors with a full crew.

“This will transform how live-action productions can be conceived and planned,” elaborates Mack. “We can use VP from the earliest stages, with the entire team referencing the same 1:1 accurate scan of locations. In addition, we’ll be building software to best enable this process.”

Learn more about workflows in our article about the future the production pipeline.

This article appears in the July/August 2025 issue of Definition