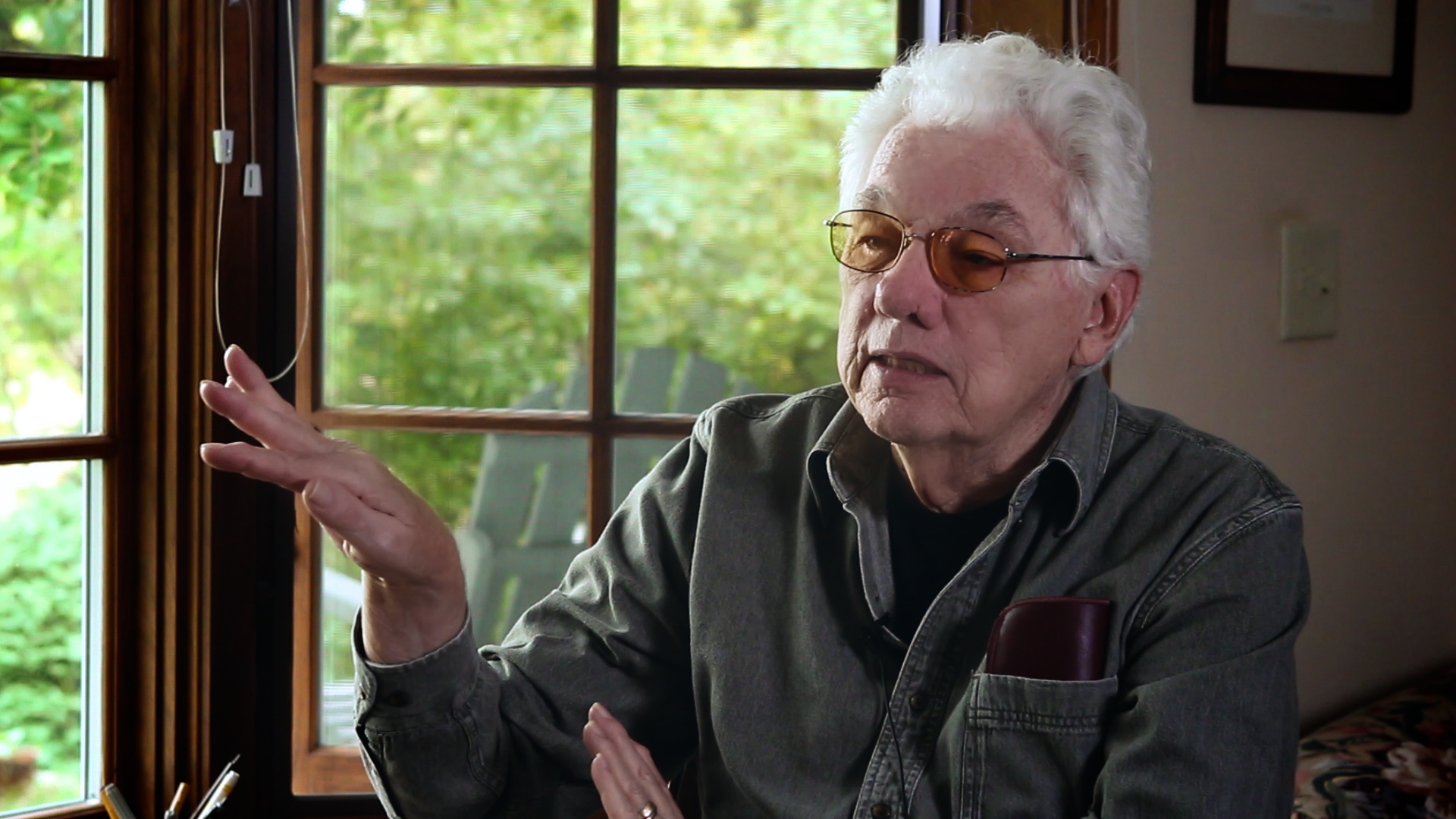

Interview: Gordon Willis – The ‘Walk And Talk’ Guy

Posted on Apr 4, 2013 by Alex Fice

Retired veteran DoP Gordon Willis recalls his work in this fascinating interview from crafttruck.com

In association with crafttruck.com legendary DoP Gordon Willis recalls the films, the directors and the techniques which awarded him an honourary Oscar in 2009. He talks at length about his relationship with Woody Allen and Francis Ford Coppola and about how he managed to capture some of the iconic imagery in cinema today. Interview by Jeff Glickman.

Jeff Glickman: If you look at the history of film, there are some extremely memorable images including the shot of Marlon Brando at the beginning of The Godfather with dark pools under his eyes and a man asking essentially for blood justice. Did you know that you were making history?

Gordon Willis: Basically you don’t know any of those things when you’re working. You do what you want to do, make what you’re doing at that moment work. I never thought of anything as being iconic. If you look back at a movie and everyone’s had a good time, it’s usually a piece of junk because they were too busy having that good time.

JG: But what was so innovative about that shot? My understanding was that it was a wide soft-top source of light.

GW: Well you’re looking for the formula. There is no formula. The formula comes out of you. So whether it’s a top light or some other thing, it just happens that it was necessary to do it that way. Bottom line is that the design behind all that or the thinking behind the design of all of that came out of Marlon Brando. Marlon had this makeup stuff that he was using so a top light seemed to be the most effective way of dealing with him. You don’t really want to see his eyes, there was a big Hollywood rush about it, ‘You can’t see his eyes!’. That’s right! You can’t!

“Until we revealed them a little bit later and we began opening things up a bit. But you can’t just do it for him, you have to send it in to the whole feel of the movie. The principle idea was to start in this cave-like environment, this blackness, and slowly begin to reveal and then ‘pop’ there he is. The essence of this kind of bottom feeder (the undertaker in the initial scene), cut against this wedding that was going on outside. So we had this juxtaposition of this bright, hysterical scene cut against going back to the dark room.

“It was only 20 minutes before the movie started that I decided how to do it and how ultimately the movie should look. You have to know your craft in order to define an idea. In order to take something and put it up on the screen. If you don’t have any craft you can’t do that. A lot of craft sets you free to put things together the way you want them. So I just think about what it should look like, I don’t care what anybody else did, I’ll do what I think is appropriate for the movie.

“But a lot of women didn’t like it in the business, they would say ‘He’s not so good with lighting women.’ Which isn’t true. Women would take a ‘bath’ with me in a scene where the story was more important than ‘How do I look?’ But when it was important I fixed it.

“So there is no formula but everyone tried to get the formula. I got a call from a famous DP at the time. He told me that somebody wanted him to shoot a movie like The Godfather. He asked me how I did it. I told him I couldn’t really tell him, but he says, ‘Well there aren’t really any secrets in this business.’ I agreed but told him there was no way I could explain it to him because there is no process, there is no formula.

“The first thing people do when they start is to do things that they have seen other people do. Which is mostly not good. But once you push past that and start having your own ideas like using a single light bulb while people move through the scene, for instance. It may be good for you but for everyone who is paying for this – major coronaries. The first week of The Godfather with the opening scene of this guy in the room. The producer comes up to me and says ‘Is this too dark?’ I said ‘No, if you make a cut, you don’t make a cut so you can linger on the cut. This cut is designed to work either ahead or back of or next to another cut.’ I said ‘You have to look at it in terms of everything, when you see the rest of it that goes with this I think you’ll feel better about it.’ This is how you have to explain everything.”

Influences

JG: What were your influences?

GW: “I was always watching movies, I grew up with the movies and I began to enjoy great black and white movies. Most of what learnt about cutting I learnt from watching films. You learn a lot if you watch movies that were made in the thirties or forties. You’ll see a shot of two people arguing or talking about making love, head to head it goes on for five minutes, there’s no cut in it. It plays really well so why would you cut? So I learnt a lot of that kind of structure from watching films from earlier directors and DPs but if I think back on it I enjoyed black and white movies more than colour.

“When you work in colour it’s a burden. You have to deal with colour, if you don’t deal with it it’ll turn in to something awful. You can’t just let people put anything on they want, it has to be coordinated and focussed otherwise it looks like an explosion in a ‘Sherman Williams’ store. But new things that we have to cope with like 3D usually point to the fact that nobody is going to movies anymore. They will say things like ‘It’s not big enough or wide enough.’ In my mind these aren’t the real reason, the real reason is that there is no narrative. We are in a world where people perceive complexity as a good thing. Complexity is not a good thing. People don’t understand the elegance of simplicity, there are a very few people left who do understand it. If you take a sophisticated idea and reduce it to the simplest terms so it’s accessible to everybody and don’t get simple mixed up with simplistic. It’s how you mount and present something that makes it engaging. Simplistic is doing it badly. Simple is your choices. One light coming through a window might be quite beautiful and it might be all you need, you don’t need six other lights. You have to ask ‘Why are you doing all of this? By habit or by need?’

“Usually what happens now is they take a simple idea and tie it in to knots until nobody knows what the hell is going on. As long as they blow up something every 20 minutes.”

Woody Allen

JG: There is story that you and Woody Allen were talking on the set of Manhattan and he says to you ‘Gordon you can’t see the actors!’ to which you said ‘Don’t worry you can hear them.’

GW: That was based on us going a piece in Manhattan where he and Keaton are in her apartment and he’s whining about getting something and we were talking about the blocking. I said to let her say this line and you then leave the shot and then you come back in and she leaves the shot. He must have like the idea as he used it many other times. He said ‘But I’ll be off screen, they won’t see me.’ I said ‘Yes but they’ll hear you.’ A light bulb went off in his head and he says ‘This is great!’ It was better to do it that than to be nose to nose in the scene.

“Also another scene in Manhattan in the apartment, the Hemingway one, I walked in to the room, the location we were going to shoot in and I said ‘How about doing this in one piece’, he enjoyed doing things in one piece. I said look at the way it’s laid out, it would be very nice presentation on the scene. The shot carries the scene, we’re not pressing an issue here so lets just do it this way. You could cut to her and then to him but you wouldn’t have the same kind of magic in the scene.

Career

“I shot two movies a year for a while but was out of work once for six months, but that was in the early days. But when you do certain kinds of movies with certain kinds of people in a certain kind of way you automatically separate yourself from the business as a whole. So you get on a list with people who actually want to do certain kinds of movies a certain kind of way. As opposed to ‘Get me somebody who can get this done in eight weeks!’ I’ve done those too but that’s not why they usually hired me. They hired me to design a movie, structurally and visually. All the directors that I worked with wanted a lot of input for everything except the acting part which I never dealt with although I had good relationships with actors. Of course I never get involved with the editing after the fact but in order to shoot you have to know how to cut. It’s a lesson for directors which I wish more of them would learn. You don’t need a cut at the door knob and the window… Medium shot, long shot, over the shoulder… That’s ‘dump truck’ directing as I call it. They take all this stuff and then throw it into the editorial room and the editor fashions the movie. I never functioned that way.

“Take a mythical movie, you read the script and you break down the script in your own mind and you go over it carefully with the director to see what he wants. Some directors don’t do that at all. Finally what it boils down to, you walk in to the first set of the day and what I do is, lets say you have three pages, is to work out how many cuts do we need to make the scene work. What’s the scene all about. It may turn out that one cut does the whole scene. Effectively, this has nothing to do with economics, or you may need three cuts.

JG: An example is maybe again in Manhattan where Woody and Diane are walking down the street and then go into the convenience store. This is where they start to flirt a little bit.

GW: “That sequence was put together before we started shooting it. So all those cuts were in my head and Woody’s. I love those shots, it takes a long time to set them up but actually it works effectively in the end because the shooting goes faster.

Annie Hall

JG: When you speak to some cinematographers about Annie Hall, they say that this is the film that has no lighting.

GW: “Well that’s a poor example in my mind but I’m glad they feel that way. A large percentage of my movies look that way.

JG: One of the walk and talks for instance, are there lights there?

GW: “No, you have to see what you’re looking at. I don’t shoot by habit. Lets just try it, we’ll hear you to begin with then you’ll materialise. But there are no lights there. Most of those exteriors I rarely put anything up.

“I did a lot of blocking for Woody. Yunno discussing the way scenes could play in a room. If you look at those movies and way he moves in and out of the rooms are based on suggestions I made to him based on the blocking. Blocking coupled with the camera becomes an instrument of telling the story. You also make that choice because of what the cut is before and after. He would come up to me with the script and say what about this or whatever and I would turn the page as I wanted to know what happens afterwards. You have to have the whole movie in your head at the same time.

“Blocking is extremely important when you’re making a movie because you want it to deliver information. Imagine a scene, you’ve worked out three cuts, you’ve marked them all and sent the actors away. Then I would light primarily for most of it except for the little things. I was finished, we would just have a tech rehearsal for the sound and then shoot. If there was a close-up I would make adjustments if necessary.”

JG: Why was it, in the fifties and sixties, so common to see very ‘stagey’ lighting with triple shadows. On The Great Escape for instance, it just looks like a set. What changed that got rid of that aesthetic?

GW: “I changed a lot of it. A lot of these people never really thought about the scene. Most of the thinking was ‘This is so and so and Steve is in it and so on.’ Their first obligation was first not to get fired but also to the studio. They ended up doing things a certain way that was always the same and acceptable. Of course you’re also dealing with contracts, people are stars. For instance Joan Crawford always had her own cinematographer.

“I actually mean that I changed it because I started re-defining things based on what the story was, what was happening in the room. It was always hung on ‘Was it OK for this moment in the story.’

JG: There was a scene in Godfather II that you are quoted as saying that you may have gone too far with the under exposure.

GW: “Was happened technically is first of all Eastman Kodak can’t make film anymore. They don’t want to make film anymore. When they were making it I always depended on repeatability. If I ordered something there I always knew I would get that. Repeatability in labs was much better but that got really dicey after a while. Then the film got really dicey. So when I saw a lot of those scenes they were three strips, they were printing three strip technicolor prints. So a black on a three strip print was ‘black.’ It was beautiful. Your movie would look the same all over the world because the same matrixes go to Rome, to London etc… Removing three strip printing from the process made it more difficult to get it to look what it originally looked like. I couldn’t never get the original back even when I was electronically re-assembling the movie. They then sold the first two Godfather movies to the Networks and they did what they wanted to them. The bottom line is that you can’t always depend on anything anymore.”

JG: How did you get along with Francis Ford Coppola?

GW: “We didn’t always get along because I deal with specifics, I don’t want to know about feelings. I deal in layouts, you can’t shoot unless you block a scene. I was very instrumental in doing that all the time and it was very frustrating for Francis as he still had this kind of film school mentality. He would admit to that. We had a lot of problems in that way.”

All The Presidents Men

GW: I’m very proud of that movie as it’s all about delivering information. Every shot, in principal, you were delivering information. When you look at it we did a damn fine shot of doing that and not making it rudimentary. The news room was a bad place to work as that got very oppressive. I don’t know how people work in florescence all day. Imagery became very important, the size of the imagery, what you cut to and still be able to deliver the information. There was a lot of things happening at the same time, it was an in-depth movie. I actually had some diopters built for that movie and had a holder built for them so they could be slid in and out during a shot. There was a shot with Bob (Robert Redford) with a lot going on in the background, that’s the scene I had them built for. We’re zooming in on him and we were able to maintain focus on both ends. The second assistant who was to push them in on mark didn’t show up on the day we were going to do it, he got scared that he wouldn’t be able to do it. This was a Hollywood kid!”

JG: Another movie I wanted to ask you about was Interiors. Did you ever have second thoughts about how dark this was?

GW: “No, I knew the limitations of the stock. I shot a series of tests on this stock which ran from normal all the way down to three stops under and three over. You find the limits of the film stock and the print stock. You have to know what a stop and a half looks like because you can’t tell when you’re standing there. The problem is your eyes make adjustments and compensate, film doesn’t you have to make it do what you want. If you don’t know how to make it do what you want then…

“I worked with very difficult people and I was difficult myself, but I think they were all good people. I finished working because I got tired of waiting in the rain for actors to come out of their trailers. But you also run out of people, the kind of directors that have an elegant head on them and know how to tell stories. Walk and talk movies is what I did.”