Lens logic: Femme

Posted on Jan 14, 2024 by Samara Husbands

Femme: Lens Logic

Neo-noir thriller Femme follows two gay men as they wrestle with identity. Katie Kasperson hears from DOP James Rhodes on how both storylines were visually established

Images © James Rhodes

Despite its title, Femme is largely an exploration of masculinity. Adapted from their original short of the same name, writer-directors Sam H Freeman and Ng Choon Ping place two men at Femme’s centre – Jules (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett), who’s a part-time drag queen, and Preston (George MacKay), who’s closeted.

After Preston incites a homophobic attack, Jules finds an opportunity to exact revenge – and what could’ve been a predictable story becomes a compelling look at power and fragility.

Seeing double

To differentiate between Jules and Preston’s distinct storylines, James Rhodes – Femme’s BIFA-nominated DOP – created his very own ‘lens logic’. “I had a theory: let’s go anamorphic for Jules’ world and spherical for Preston’s world,” recounts Rhodes. “The aesthetic of [anamorphic] lenses is often quite considered, planted, controlled. And then spherical – you can kind of do anything.

“I wanted to lean into that as a theory which reinforces, subconsciously, the sense of threat the characters are experiencing, in the same way a score often does. Preston’s world is spherical, which tells the audience that anything could happen at any time. The language of the camera was much more visceral and reactionary.”

When the film begins, the audience primarily sees the story from Jules’ perspective, opening with a drag show that establishes him as being strong and self-assured.

“That Steadicam shot out from backstage – it’s an exciting shot, and sets up prestige around the Jules character,” explains Rhodes. Minutes later, after an encounter at a corner shop, Preston attacks Jules, leaving him crumpled on the pavement. The drag show then assumes new meaning: “it establishes what’s been lost and why there’s so much at stake when it comes to trying to regather [Jules’] confidence.”

Rhodes shot Femme on a Sony Venice cinema camera, despite initially leaning towards 35mm film.

“With the budget, it didn’t quite work out,” he describes. “Retrospectively, I’m incredibly happy it didn’t because we would never have been so bold as to shoot anamorphic and spherical. We wouldn’t have carried two cameras just to be able to flip-flop between formats.”

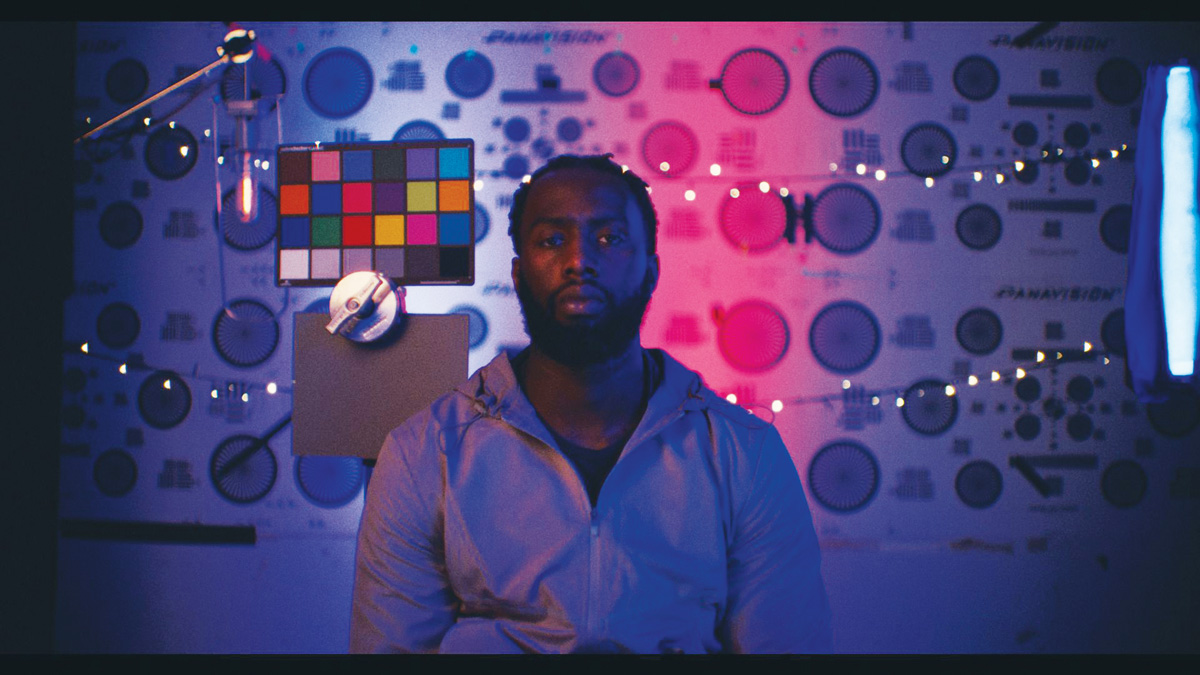

Rhodes alternated between a Super 35 50mm high-speed anamorphic, large format 40mm Ultra Speed spherical and the Super 35 PVintage spherical lens line – all supplied by Panavision London.

“Jules was anamorphic if he was safe or feeling confident,” begins Rhodes. “But when he went out and was exposed, we were into the 40mm spherical land. Then, if he was with Preston and even more vulnerable, it was all PVintage.”

A few months after the attack, Jules notices Preston in a gay sauna. Realising that Preston doesn’t recognise him out of drag, Jules takes revenge by seducing – and ultimately outing – Preston via a secret sex tape.

From then on, Preston becomes a central character, inviting the audience into his psyche, which is juxtaposed through handheld camerawork. Initially, he’s aggressive, guarded and viewed from a distance.

Although, as the story progresses, we see him afraid of being exposed, especially to his friends. Rhodes demonstrates this arc through lens changes. “As Preston becomes the co-protagonist, he takes on the same lens logic as Jules.”

For good reason

For Rhodes, it was more than just glass; from lighting to colour palette, everything needed a purpose.

For instance, the vast majority of the film takes place at night, besides two key moments of early-morning daylight – one towards the middle and one at the very end.

“[The directors] always wanted the story to happen at night, until the moment that everything changes,” explains Rhodes. “That’s the first glimpse of daylight we get – and it’s only brief. Basically, when Preston becomes a protagonist himself, we wanted to breathe for the first time.”

“Being so nocturnal was part and parcel of it being stressful and never coming up for air in a way,” continues Rhodes. Films like the Safdie brothers’ Good Time, Fight Club, Hustlers and A24’s Waves all served as visual influences, informing the use of colour, particularly neons, to saturate nighttime scenes.

Rather than giving over to pure aesthetic appeal, every choice was considered. “I find it challenging, always trying to put what feels like unmotivated colour in scenes,” admits Rhodes. “I constantly had to be giving myself a logic for the light sources, just so I could really lean into them. Once we had that, it was great because it was like, ‘Hey, this is the purpose’.”

Real deal

Above anything else, Rhodes and his crew wanted Femme to feel real.

“We didn’t want it to feel perfect. It had to feel tangible and realistic like east London,” he shares. The production team achieved this through practical, in-frame lighting and an absence of computerised effects.

Femme is full of interesting lighting from lamps, candles, refrigerators and televisions.

Rhodes explains that ‘the use of practicals was always to give freedom to the camera’. By mostly avoiding floor lights, “the camera could always react to the scene and become more organic. It makes everything feel realistic when you pan around and see where that light was coming from. We retained that aesthetic of feeling like a real environment.”

Because Stewart-Jarrett and MacKay have vastly different skin tones, the crew occasionally needed to introduce low-intensity light sources near or behind the camera.

“Those subtle reflections in Nathan’s skin gave us texture without over-lighting him or other characters in-frame,” states Rhodes, though he otherwise lit them identically. “Often, there can be a misconception that if [the actor has] dark skin, they need more light so that you can see them. It’s actually nonsense. To put it briefly, I didn’t treat them very differently.”

Several of Jules and Preston’s interactions occur inside Preston’s car.

Rather than using a green screen or an LED volume, “everything was old-school, put it on a trailer and go,” says Rhodes. “Again, leaning into trying to make stuff feel as real as possible, I wanted to expose the characters as much as I could with the environmental lighting from outside. So [I was] working at really low light levels – basically cranking the ISO as much as possible.”

Give and take

Enjoying a varied career which includes live music, Rhodes compares filmmaking to ‘playing in the band’. “I feel like I am participating,” he enthuses. “My camera operating is always feeding off what the cast is giving me. We were all properly in lock-step with each other.”

With Femme being their first feature, Freeman and Ng were ‘inexperienced but also confident’, according to Rhodes. “It was rewarding because they gave so much creative control to me and trusted me. It meant I could create something I felt really excited about.”

Femme is out in cinemas now.

This feature was originally published in the January 2024 issue of Definition.