High Frame Rate War

Posted on Jan 3, 2017 by Julian Mitchell

In our last look at the most technically awaited movie of the year we talk to director Ang Lee’s right-hand man and fellow pioneer in high frame rate cinematography, Ben Gervais. Words Julian Mitchell.

So we saw it. 12 minutes of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk in glorious 4K, 120fps 3D. The feeling was amazingly intense especially for the battle scenes. Seeing everything doesn’t explain what 120 frames gives you, but one scene brought it home to me. An American soldier is firing his heavy machine gun at the enemy, while he is shooting the vibration going through his body gives him an aura of dust surrounding his body shape. That is a new reality for me. You definitely felt like you could reach out and enter the scene, just walk right in there.

What were other people’s feelings? 3D expert and filmmaker Phil Streather said it was, “Very visceral, I felt tense. Good 3D. Was it better than Saving Private Ryan? Not sure. Sadly there was some crap acting in key roles; the sergeant, floor manager and assistant floor manager at show. I don’t think the acting issues were “revealed” by the 120fps, however, they were there at any frame rate.

“The best bit about the clip was the brightness for the 3D. That was due to laser projection rather than HFR. I would hazard that 24fps at 12ft lamberts would help the 3D more than 60/120fps at 5ft lamberts.”

For those of you who don’t know, we are talking about shooting in high frame rate, more specifically 120fps not the 48 of The Hobbit or the 60 of director James Cameron’s test.

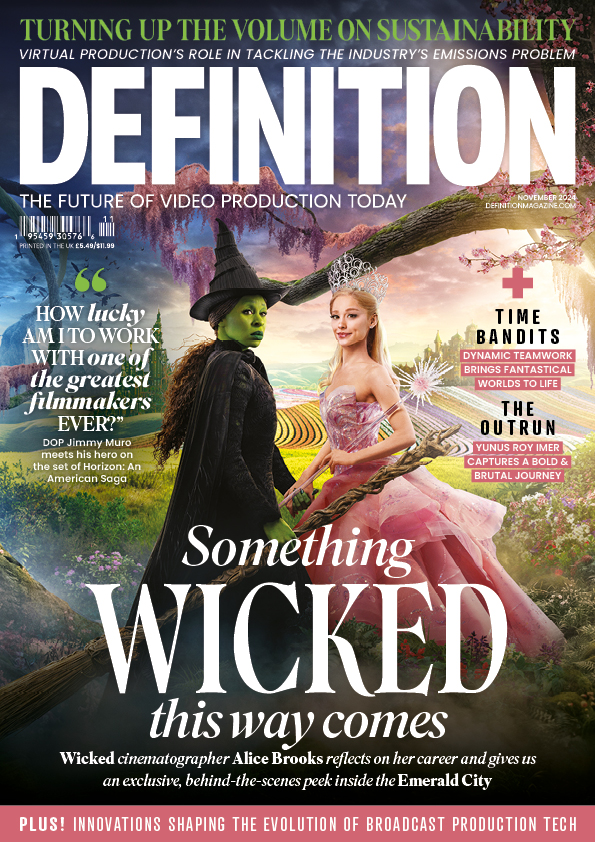

Director Ang Lee and ‘Billy Lynn’ actor Joe Alwyn.

Director Ang Lee and ‘Billy Lynn’ actor Joe Alwyn.

Ben Gervais was the film’s tech supervisor and he was as surprised as anyone when Ang Lee moved past 60 frames and then decided to double it without even knowing what it would look like.

“Ang gave me this mandate of shooting in 120fps, but how do we give people an experience in most of the theatres that aren’t going to show it in 120, in the 60 frame and 24 frame theatres. So he said ‘Give me 60 plus, give me 24 plus. Make it as good as you possibly can as we’ve got all this data from the 120 shoot.’

“We tested it with Ang in an emotional way, not just technical. So to have someone who doesn’t care about the technology is quite refreshing because he doesn’t care how we got there. If he was satisfied with 60 we would be at 60, fundamentally we would push until Ang was satisfied.

The team’s original thesis was just for 60 frames but there were some technical challenges just for 60. For instance how do you derive a 24-frame version of the movie from 60? “There have been tests done, Ang did a test. But one of the issues is if you interpolate down to 24 then you are going to have to ‘fix’ the 3D and touch up with VFX which means every shot in the movie becomes a visual effect and that’s obviously not cheap. This is not a huge-budget movie, only $40m, in Hollywood that’s pretty small.

“So one of the reasons for 120 was because we could drive the 60 and the 24. Then the questions started coming up like ‘What do we think 120 looks like’? James Cameron did his test at 24, 48 and 60, pretty much everyone’s done their test at those frame rates, nobody had done a test at 120. Doug Trumbull had done his thing but it’s a different kind of 120 than actually doing it pure both eyes shooting 120fps. Doug is a total inspiration for us though; he’s got a pragmatic approach and he wants to make it work for every theatre.

We wanted to explore the frontier. Doug is just trying to make 120 work for everybody.”

Shooting Blind

Just to illustrate how much of a risk Ang and Ben were taking with a HFR approach to the film. A week away from principal shooting they still hadn’t seen a test. “We didn’t know what it looked like until a week before we started shooting because we couldn’t get the projectors and we couldn’t get the servers. We’d shot a whole bunch of tests but could only watch them at 60. So we convinced Christie who were very kind and super supportive and they brought us two laser projectors. We shoehorned them into our tiny little projection booth that we had built in Atlanta for our movie – we only thought we’d have one projector in there! Then there’s a whole laser bank that has to be attached to them. We got a loan of some servers then had to figure out how to conform a movie at 120. Our very first version of the conform was actually in Excel.

“The problem with shooting at 120, with Sony F65s, is that they don’t start on the same frame when you push record, they don’t stop on the same frame when you push stop; they don’t have the same timecode and it’s usually about three frames off but sometimes it’s more, sometimes less. There’s no reliable way to know and it’s running 24-frame code but at five times the speed, so it’s the ‘Wild West’ really. I had to have my lab technicians record the matching first frame in 3D and then build a database of every single take of every shot. Editorial wanted to run at high frame rate because we wanted to get as close to what Ang was trying to do as possible when we were in the editorial process. The fastest that the AVID will go is 60! So we delivered every shot as if it was a VFX temp so they all start at Zero frames.

“We built this database and did a proof of concept in Excel then migrated it to Google. So we take out the 60 frame EDL from editorial, we had to go all the way back to old CMX EDLs that they had to use in the seventies. We’d upload that into the cloud and I had to write code that goes through and finds the matching eyes, knows what the 60 code is, translates that into 120 frame code and then calculates the offset because both cameras didn’t start at the same time. Then the code generates two EDLs, one for the left eye and one for the right that allowed us to do the conform.

“So we figured out how to do that, then we compiled some footage; we had to render it at that point into a special format for the servers, they wouldn’t take DPX files, now they do. They made some changes for us. We took that footage, we loaded it onto the servers and put it on a screen.

“So we finally got it on a screen and even before we were able to calibrate the projectors Ang was very excited and wanted to see it. So he came in and none of the colours were correct as lasers take a little while to calibrate. But we threw an image up and hit play and all of us just stood there in stunned silence for a second. We all had theories of what it would look like but no one had ever seen it before on the planet. The guys at Christie, who are the only people that make these projectors and only show CGI-based 120 stuff, were there and we all looked at something that was totally different. We had theorised before that the bump from 24 to 48 is pretty significant and the bump from 48 to 60 is significant but not as much as the one from 24. So maybe 120 would be just a little bit better than 60. You are getting up to where the optical scientists call the critical flicker fusion frequency where you can’t tell the difference between something that’s solid and something that’s flickering.

“But what we saw on the screen was something totally different. I could talk about it for ages but it’s not until you see it that you know it’s so different. We then tried to take things away and first thing was the brightness. At that point the lasers still weren’t calibrated, the red lasers were running at 100% and it was a really bright image. Ang went away after we watched it and we set the primaries correctly and brought the brightness down to 14-foot lamberts which is the 2D standard. Ang came in the next day and we sat down and watched it and he said, ‘what happened?’ We said that we’d calibrated it and it was now in spec. He said that he didn’t care about the spec and to show him what it was like yesterday with the colours fixed. It turned out that we were probably around 28-foot lamberts to the eye and not 14 when we had got it calibrated and stable the day before. We pushed it back up to 28 and straightaway there was something there. We experimented to and from 4K to 2K and again it sort of lost the life that it had. So it seems to be a combination of things.

“Once you get 4K, 3D, 120fps and high brightness you’re seeing something in a different way. Ang feels that this is what digital cinema is. Up until this point digital cinema has just been mimicking film cinema. We’ve been using those tricks we’ve learned and been rolling them in different ways but it’s the same parts that we’ve been rearranging.

“But this is something different, we have to go back to the drawing board for everything we do. Every department has to step up and we have to learn again. But that’s great as you’ve got no one to call because no one has done it before. You begin to realise how tight the tolerances now are; you can’t do the stuff you used to do.”

Predicting The 120 Effect

The team only had the Christie projectors for a week so in that time they decided to look at scenes in 60 as well as 120 and hoped to learn what something in 60 would mean in 120 when they were on set shooting. “The dailies viewing was only 60, we couldn’t get the projectors for the filming. What it did mean for all the crew is that details matter, you can see that much more shooting 120.”

Ben had seen all the HFR tests over the last few years which of course included Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit films. There was a feeling that the 48fps of these films looked too much like television but Ben felt that the blame lay elsewhere.

“Peter Jackson is a groundbreaking director and he tried something shooting The Hobbit in HFR, but I think it was the wrong material to start with. The first thing we said is that we need real locations because it’s so much harder to make a set that looks real, you just go to a real location. There are a couple of sets in the movie but for the most part it was the real thing because we wanted it to look real.

“Again given our budget level what could we do, knowing that there’s this absolute need for precise detail, to make it work? If we could get away with it we weren’t going to put make-up on the actors, the set people had to really concentrate on the few sets we had and pay attention to the fine detail that we would normally gloss over a little bit. We changed the lighting, we changed everything for this dynamic to make it appear more real.

“It was particularly hard on the actors as you can tell when they’re tired and hot. At 120 you can tell between an actor who is just waiting to say their line while someone else reads their line or if they’re actually listening to the line before they deliver theirs. Because you can actually see what their eyes are doing. At 120, 4K stereo you can look into the eyes of an actor and actually connect. While at 2K and 2D it just a picture of a person. So it’s a different type of experience – it’s really intimate. Some of the few complaints we have had were ‘it was too intimate and intense; we were too close to the movie’. I’ll take that as a compliment.

“If you want to be detached this isn’t the format for that. It’s an engaging format; you’re drawn in. The movie’s very much from Billy’s point of view. It wants to put you in Billy’s shoes and for you to take a side with the war politics that are in there. We’re trying to show you in a small way what these guys go through.”

Data Torrent

If you’re tech supervising a digital movie or high-end drama you are always going to be weary of the data impact. That’s why specialised companies are now sprouting up to babysit the whole data journey. For Ben, his data plan was off the chart. “We had 120 512GB cards for the Sony F65s. It was easy to see that we had to make the choice early on to build our own workflow. The reason for that was when we’d talked with a couple of the post houses they were very enthusiastic but at the same time they didn’t have the ability to pivot to what we were doing so much. This is a whole new workflow, the amount of data is so huge, we ended up shooting on average 7.5TB a day, some days were as heavy as 15TB or 20TB. We would have taken over the post house, they wouldn’t have had anymore clients. Then we would have had to re-engineer all the resources that they had. It seemed to make much more sense to customise something for what we were doing.

“My first thought was that this was a huge volume so we’d have to do everything in parallel. You can’t have one expensive special box that just does something, because we’re going to have to funnel all our dailies and our post workflow through it. I tried to focus on commodity hardware and ended up employing a lot of VFX workflow tools because they are used to rendering in parallel. So we created three separate pipelines in our dailies process so we could have two pipelines go down and still be working. It would be slower but at least we’d have some redundancy there. The three machines were doing ingest of cards, checksums, then we put the footage onto our SAN and from there it would get rendered out using the Sony tools to generate QuickTimes for 2K in each eye. We would frame blend that down to 60 on the render farm then we would push that in to three Colorfront systems to add colour and to sync the sound and generate all the deliverables from there. We had three guys running that basically and fourth to help set it up. Generally, our turnaround time for dailies was about 12 hours.

“We built it first in Atlanta for the stage we were shooting in, we built the theatres for the dailies. One of the bigger challenges that we knew about from the beginning was going to Morocco to shoot the war footage. Our schedule and our budget was really tight so we had five days to make the move. We had two days to pack the lab up and the camera team and all that stuff, all the cameras and all the 3D. We had one day to fly with it, two days to unpack it and get it ready and we needed to be shooting the following day. Then we had seven or eight days shooting there.

“In all we shot for 49 days and got about 400TB. It’s compressed 6:1 and was shot at 60fps. It’s not lossless; the way the F65 sensor works is that above 60fps it only samples every other line and then it compresses the remaining data 3:1. That’s one of the reasons that you can’t use the internal NDs above 60fps because it actually puts a new OLPF in front of the sensor to mitigate the aliasing artefacts from sampling every other line. So you end up using NDs on the mattebox but then you have to realign the rig every time so the preference is to not do that if you can get away with it.

“Generally the low-light scenes were a struggle, when you bump up the ISO on a camera obviously you increase noise too. On the lower frame rates you can reduce the noise by averaging it out, essentially you’re adding frames so you can actually reduce your noise floor. To go to 120 you’re down around 2.3 stops, you lose another third with the beam splitter on the 3D rig. You get it back because you’re shooting 360° shutter. So from 800 ASA which is the native rate of the F65 you’re down to maybe 160. That’s not ideal. So we did some test shots where we bumped up the ASA and then we did some noise reduction on those shots and we A/B’d them with the no-noise-reduction footage. We just happened to have the 120 projectors there and it was amazing as we couldn’t tell the difference. We didn’t understand what was going on, then it became apparent after retesting to make sure we were doing the test right. As it turned out, at 120 frames the noise is going by so fast your brain doesn’t register it. It was really interesting and we realised we could get away with some stuff. There are some scenes in the movie that were shot 1600 ASA and I had some VFX artist calling me over and wondering what they could do with the noise. I was saying do your best to match it but don’t worry about making it go away because we don’t need to.

“Also every version of 120 went through the RealD process of True Motion to further help lessen the noise of the look. But it also gave us creative options like customising the amount of motion blur between scenes or into a frame. You don’t have to involve VFX at all for this. Before if you wanted to change the amount of motion blur in a shot you would have to send it out to a VFX vendor. Every time you do that it costs money. We just rendered it out with say five different types of motion blur put them all into FilmLight BaseLight. You use a window and so you have one type of motion blur on one part of the frame and another on a different type of motion blur. You then just see what it looks like. If you don’t like it the cost is only a little bit of render time.

“It’s almost intimidating the amount of control you can now have over an image. For a filmmaker it’s empowering as you have all these new tools you didn’t have before. You can do some of it in-camera but then you have to commit to it. Having said that we must have the utmost respect for people who commit to these looks. Being on set is where you seize these opportunities.

Mixing Frame Rates

Those who have seen the full 120fps sequence have wondered about using it for an effect, say for a war scene or something that would benefit from the look. You could then shoot your main drama in 24 as usual. Ben had thought of this in his original thesis but then did some tests.

“I decided to mix some different frame rates with different shutters over some two-minute tests we shot on the back lot. I put the 24fps version up first and told people that it was that. Then we cycled through the others and I put the same 24 version on at the end without telling them. When that came around the second time the reaction was, ‘Oh, god, what is that? It’s horrible’. We didn’t have any response when it was there at the start. It was the judder that affected people so much, from not having it to having it was the reason. It was unacceptable but at the start it was what we were used to. Now because I’ve seen so much of the 120 I can’t watch normal 24 frames without being affected.

“So if you are going to mix frame rates you have to be very careful about how you do it because your brain adjusts and then you see something that used to be acceptable but it’s not anymore. The approach has to be very gentle.”

Movie success?

The question, of course, especially after the lukewarm reception of The Hobbit is, will HFR become a success? The marketing teams at Sony are obviously nervous and have even tried to stop us writing about the movie in these terms. Even Ben thinks it could be very good but could also not go so well.

Personally, I think the story is so strong that the movie will be a hit. But if it fails you might see HFR quietly be shelved for a while, Ang Lee is worried about this too. He thinks that studios will say that if Peter Jackson and Ang Lee can’t make it work, who can?

Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk will be out in the UK in February 2017.