Bigger Bit Buckets: fast storage

Posted on Sep 6, 2021 by Alex Fice

When everything records files, camerawork starts feeling more like being an IT specialist. Some of the pain, though, can be taken away by choosing the right IT – but a number of those choices aren’t straightforward

Words Phil Rhodes / Images various

Let’s start with an enlightening comparison. HDCAM-SR was the last in-camera tape format. At full throttle, it delivered 880 megabits per second of data. A 124-minute tape therefore contains around 800 gigabytes of data, at a cost of around £300 each. A one-terabyte flash device, such as Samsung’s 970 EVO Plus, is 30 times faster, holds 25% more, is a third of the price, a fraction of the size and weight, and doesn’t require a five-figure playback device.

That’s something that makes camera technicians very happy, faced as they are with a need to handle the huge data loads of modern sensors and Raw recording. Long-term archive is a vexed question, but the on-set end of acquisition has a lot of options. Perhaps the biggest surprise is that some of those options still include spinning disks – but let’s start with that big, scary Samsung drive, the 970 EVO Plus.

High-capacity circuit boards

An M.2 device is really a component, a circuit board –something that might go inside a housing to become a stand-alone storage device, or be plugged into a workstation to hold the operating system or temporary data for a non-linear editor. Some proprietary storage devices used in cameras have also been based around M.2 drives. There’s only so many ways to package up flash storage, and there are as many pocket-sized devices as there are pockets.

The company’s portable SSD X5 (£240 or so) is one such pocket-sized, Thunderbolt-attached device, that will store data at around 2300MB/s per second. That’s the equivalent of shooting Alexa LF Open Gate at over 100fps, and the camera will only do 90, so it won’t be a big problem to keep up with downloading cards. The X5 might reasonably be despatched to a post house on a bike, and so might the T7 Touch (£200, or a little less). It’s slower at about 1000MB/s, but an even more compact device, with USB 3.2 Generation 2 connectivity. That highlights one of the wrinkles in storage: plug it into the wrong socket and the device is hamstrung, so selecting the right socket demands attention to detail (see the problem with USB).

Slot-in storage

Things are a little simpler with SATA-attached devices. While SATA was originally intended to connect hard disks to computers on at least a semi-permanent basis, it’s become a popular way for on-camera recorders to use off-the-shelf flash. In some ways, the baby of Samsung’s range is the 870 QVO, which is limited to speeds slightly under 550MB/s by the SATA interface, but it does slot straight into a variety of useful devices.

All these flash options store up to a few terabytes, but that won’t satisfy a multi-day 6K shoot, recording a high-quality format. Even in 2021, not everything can reasonably be done with flash; spinning disks still have a niche. With that notional Alexa thundering along at 90fps, we’re generating something like a terabyte per hour. On a feature film, that may not seem too scary – for two cameras, perhaps a couple of hours of rushes every day, if the director is enthusiastic. But it’s trickier on a week’s safari for a nature documentary with three cameras, and yes: people do that for Imax shows. It’s possible to buy hundreds of terabytes of flash, but your wallet won’t thank you.

The disk keeps turning

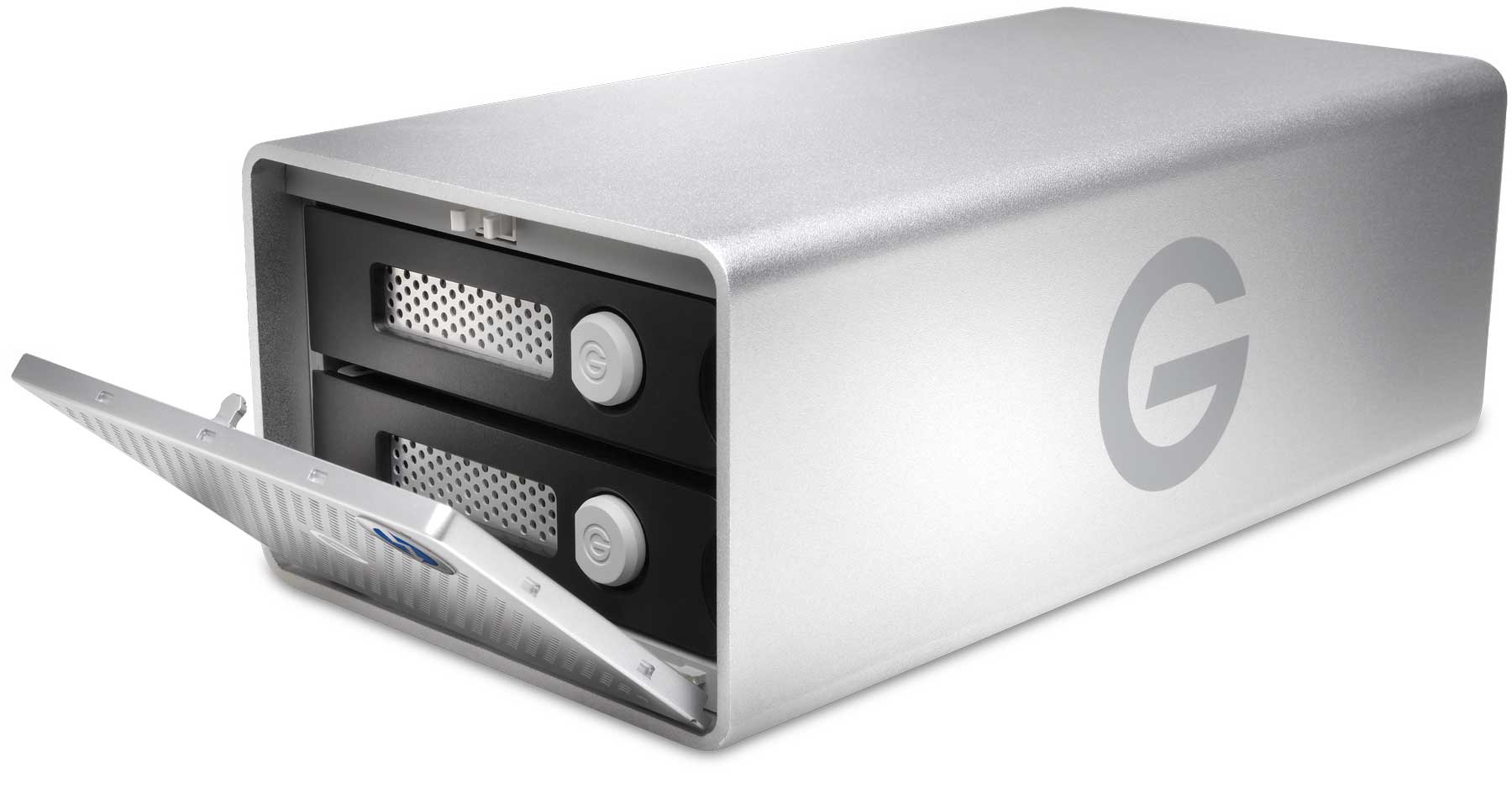

G-Technology has its roots in Western Digital, a company associated with storage since the late 1970s. It has a full range of flash storage, which is represented here by the 1TB G-Drive Mobile Pro SSD, a Thunderbolt device that competes ably with Samsung’s X5. The Western Digital connection particularly shows in G-Drives using spinning disks. USB-C models come in capacities from 4TB to 14TB, with the biggest priced at a somewhat modest £690, including VAT.

The range is based around 3.5in hard disks, the type traditionally used in desktop computers, which has a few implications. First, the power consumption is high enough that they need an accompanying wall wart. The upside is performance: a conventional hard disk will never match the multi-gigabyte-per-second performance of typical flash, but the G-Drive range is specified up to almost 200MB/s. In the early days of HD on feature films, it took a pack of six disks to do that.

Pint-sized bit buckets

Western Digital also own the Sandisk brand often seen on flash cards. But if we’re going to talk storage, we should discuss LaCie, a name frequently found cabled to a MacBook at Starbucks. LaCie was purchased by Seagate in 2012, creating a relationship not unlike that between Western Digital and G-Technology. LaCie’s current party piece is the sleek-looking product simply called Mobile Drive – a compact and handy device that comes in what looks like a solid chunk of machined aluminium about 3.5x5in (thickness varies with capacity).

The design uses smaller 2.5in disks, a form factor originally developed for laptops. Aside from compactness, there’s lower power consumption and thus a single cable from laptop to disk, while retaining much of the capacity advantage of 3.5in disks. The compromise is reduced performance – the disks typically spin at 5400 rather than 7200rpm – though the Mobile Drive family does amazingly well, achieving perhaps 140MB/s in tests. It’s the sort of choice that makes sense for the news camera operator working out of a hotel room, but there are certainly a lot of people doing that, and the slab-like construction suggests they would survive a war zone into the bargain.

Continue reading in our September issue of Definition magazine.